This is another long, thoughtful article. You may prefer to listen instead (although you’ll miss out on the graphs and pictures) -

1 Feeling Right

My wife said something really sweet to me the other day, which left me glowing. Now, context is important here: you have to appreciate that normally my wife views me as someone who can’t tie his shoelaces without (a) getting it wrong, (b) causing excessive collateral damage, and (c) help.

I was sitting reading quite a large dense book, and she said “honey, you don’t need to read that: you’re already an expert”. Wasn’t that nice?

It was a book by Kathryn Schulz called “Being Wrong”.

In it Kathryn tells a very instructive story - a story against herself, which always goes down well. Actually she tells the same story better in a TED talk, I think.

It’s a true story about a road trip across the US that she took when she was 19. She was puzzled by a Chinese character that she kept seeing on a roadsign. Eventually her companion realises that Kathryn is referring to the “ancient Chinese character” for “picnic area”!

She explains that in the abstract we are pretty good at accepting that “we all make mistakes”,

(“to err is human; to forgive, divine”1);

and yet we don’t have much awareness of being wrong. “I can’t actually think of anything I’m wrong about”. “We’re … travelling through life … trapped in this bubble of feeling very “right” about everything.”

“Why do we get stuck feeling right? One reason has to do with the feeling of being wrong”. And she asks the nearby audience how it feels to be wrong, and elicits “dreadful”, “thumbs down”, “embarrassing”.

Now Kathryn seems a very nice person, and rather than say “Hah! Gotcha! You’re wrong again!” she says “Thank you; these are great answers”. And then points out that they are answers to a different question, which is “How does it feel to realise that you are wrong?”

So in considering the question “What does it feel like to be wrong”, when was she wrong - when she found out that it was a sketch of a picnic table, or when she was driving along for days thinking that it was a Chinese character? And how did it feel to be wrong?

It felt like being right!

Kathryn’s advice in tackling this monumental problem - perhaps the greatest one facing mankind (that’s my view, not necessarily hers) is to …

“step outside that tiny, terrified space of rightness and look around at each other, and look out at the vastness and the complexity oand mystery of the universe, and be able to say “wow! I don’t know. Maybe I’m wrong”

To put it more prosaically - cultivate an attitude of accepting that you are often wrong, and not minding so much. Good advice, I think; I’ll offer my advice, for you and for society-in-general later.

Kathryn does a great job of humanising, illustrating and provoking contemplation about the phenomenon of being hugely overconfident in our - largely poorly founded - beliefs. This is just one of the well-known systematic errors in human cognition, to which we are all subject.

2 Being Wrong - ALL the time

I think it helps to realise that we are wrong all the time.

You can’t mean literally all the time: you mean “more often than we realise”.

No, no: really - all the time.

That is just not possible. Suppose I say “I am here”; or “that switch is on. That switch is off”. Well one of those must be correct.

I don’t mean that everything you do or say is wrong. What I mean is that all the time you are operating with various beliefs about how life is, and how life works, and what goes on, that are wrong. Those false beliefs don’t always make you say or do things that are wrong: but they are always there, like a foundation that is faulty in places. You don’t know which of the edifices you are building on it will collapse, when it rests on a fault. And of course they don’t always collapse immediately.

William Osler, a famous physician and medical professor around the turn of the last century (1900 not 2000) used to advise graduating medical students that “half of what we have taught you is wrong! Unfortunately, we do not know which half”! This same good advice has often been repeated in the same circumstances. It’s an exhortation to constantly re-examine and check which assumptions about what we “know” are wrong; and to continue your own education after it is formally over. Osler studied science with an enthusiast before embarking on the study of medicine.

It is easy and worthwhile to demonstrate to yourself that you are always wrong. Just keep asking yourself difficult questions on which people disagree. If you have a firm belief one way or another, some of those beliefs will be wrong. For example …

1 Does God exist?

Many people believe firmly “yes”, and many firmly believe “no”. We do not need to know which is correct to know that a lot of people are wrong.

2 Who started it?

Some people believe that Russia started a war in Ukraine recently; some people believe that NATO started it.

Taking just those two questions, there are four possibilities for your beliefs (if you have them).

God, Russia

God, NATO

No god, Russia

No god, NATO.

How about the following poser?

3 Your seven-year-old son throws a cricket ball to you, which you fail to catch because it falls a bit short for an easy catch, and rolls behind you, where it stops and you pick it up. The easiest time for you to catch it would have been just before it hit the ground. At that moment, was it accelerating or decelerating? (… or staying the same speed)?

I don’t know how confident you are in your answer, but I think you will find that a lot of people who are confident in their answer are wrong. Now those four beliefs can be combined with “accelerating” or “decelerating” to make eight possibilities.

4 Is it a good idea to have an mRNA injection against covid-19?

With only four questions, over which people will disagree, you only have a 1 in 16 probability of being correct on all of them. Of course the extent to which you study the topics should affect your chance of being correct, but there are plenty of people who have given those 4 questions plenty of consideration, and come to different conclusions.

One more question (5 now) makes it 31 chances to be wrong, only 1 to be right … with just 5 questions! 6 questions would mean 63 chances to be wrong and only 1 to be right. How confident are you feeling? You only need 33 difficult questions to have ample room for all 7 000 000 000 humans on the planet to have different opinions. There are surely many more than 33 questions on which people disagree. Are you the one person in the World who is right about every question? Even if you were, you wouldn’t find anyone else who agreed with you!

The fact is you have never met anyone with whom you agree about everything. Consider a married couple. These are two people who probably chose someone they consider very compatible, to spend their life with. Do they agree on everything? I don’t think that question requires much deliberation!

One reason (just one) why we disagree with people all the time (even though we may avoid actually talking about contentious issues) is that we are wrong all the time!

This is a view expressed by the brightest and best. As well as Kathryn Schultz, we hear from at least three sources that Socrates was in the habit of saying

“the only thing that I really know is that (apart from this) I know nothing for certain.”

And

“The problem with the world is that the intelligent people are full of doubts, while the stupid ones are full of confidence”

– attributed to Charles Bukowski (… wrongly, apparently)!

I regard it as our role to go through life getting on with all these people - with all their strange ideas - despite the fact that you disagree with them. Realising that we are wrong all the time can help.

3 How do we feel when we disagree?

We like to feel part of a group, a team, a tribe. When two people disagree, they can feel that their world view is threatened, and either they have to “agree to disagree”, or one person will have to change their mind. We don’t like to change our mind. It takes a great deal of effort to think things through properly, and work out the knock-on effects of changing your view on that one issue. So disagreeing with people is an unpopular thing to do: the only thing worse than saying things which are wrong, is saying things that turn out to be right!

You are going out to dinner with your old friend Joe. Good old Joe. Salt of the Earth. It turns out though, that he is uninformed about issue X. So of course with your magnanimous disposition and your bountiful extensive knowledge you will give him the information he is missing. To your surprise Joe still argues his case. The others want to change the subject before you can explain it properly.

Next time you see Joe - (good old Joe, just a bit dim. He’s got this blind spot over X; but you’ve thought how to explain it better now). To your surprise you still don’t make any progress.

Time to see Joe and family again. Nice guy; he is rather obstinate though. In fact I’d go so far as to say he’s a bit bigoted. Your wife says “please don’t bring up issue X again”. You don’t want to either … but it is quite important that he understands: there are real world consequences for getting this wrong.

Still no progress. Oh dear - is it tonight that Joe and family are coming round? He’s such a sucker for that disinformation about X: it’s terrible that he is spreading those awful views.

Oh look: that’s Joe over there. Quick - he hasn’t seen us. I really don’t want to be seen with nutters (or evil people) like that.

Of course all this time Joe is feeling similarly about you! But at no point does it naturally occur to you that you might be wrong (although of course it can and often does, with some people). So how much truth is there in Joe’s idea that you are bigoted? What is a bigot? According to the first online dictionary I came across - “A person who is obstinately or intolerantly devoted to his or her own opinions and prejudices; ...". In other words - somebody who won’t change their mind when you want them to! Unfortunately our natural inclination - our faulty inclination - is to be much more bigoted than we would like to think.

Changing your mind is hard!

4 Systematic Cognitive Errors

(1) Unjustified confidence in our opinions (easily shown and measured) is just one of the systematic flaws we have in our cognition. By “systematic” I mean that the flaw biases all of us in the same direction. These flaws are so ubiquitous that even though we are pretty blind to them, and completely underestimate their extent and significance, they do make their way into everyday parlance. Of course errors are much easier to see in others!

For example - “wishful thinking” (2) is a big one. Psychologists call wishful thinking the optimism bias. If one option is more lucrative e.g., then that is the one that will be viewed as more likely to be true. In fact most of the other flaws can be characterised as “wishful thinking” in some way. So (3) “confirmation bias” – (you know, you want to check that you are right, do an internet search, and look at all the views that agree with yours) - giving more attention and credibility to ideas that tend to confirm our prejudices is due to wishing that our view is right so we don’t have to do any of that uncomfortable rethinking things.

(4) “Group-think” is the tendency to think like everyone else. You wish to think the same as others, as it’s uncomfortable to have to try and change their minds, or change your own, or to disagree.

Put together our terrible memories and confirmation bias, and you have (5)“hindsight bias” - believing that we had always thought what turns out to be true. Definitely something we would wish, rather than think we had been wrong all that time.

“Polish your shoes and iron your shirt before your interview: you know how important first impressions are”. Our reluctance to change our minds after forming an initial impression is called (6)“anchoring” by psychologists.

We think that other people think much more like us than is the case - (7) the false consensus effect: we wish everyone understood the world like we see it. (In fact since we feel right all the time, we just wish that people’s understanding of the world were as good as ours)! (I remember being surprised, as well as disappointed, when the mass reaction to the suggestion of mandating covid vaccines was not to reject it immediately on principle, a principle well established (I had thought) in the twentieth century. I had assumed, quite wrongly, that people thought more like me than in fact they did).

One way of experiencing the (8) ad hominem fallacy is to assume that people whom you think of as more expert than you are right. You wish to be able to assume they are right without checking the grounds on which they came to that conclusion. (“They’re wearing white coats though: they must be right”)!

However, as “we” knew more than a couple of thousand years ago, fools can be right, and wise men often (or always!) wrong.

(9) Priming is a large and fascinating study by itself. It’s important to get a grasp of this phenomenon, to appreciate how our thinking is influenced by subliminal events, to realise just how irrational we are normally. If you haven’t, read the best-selling “Thinking Fast and Slow” by Nobel prizewinner Daniel Kahneman. The (10) halo effect is a special case of priming. For example if a politician is good looking, we are more likely to overestimate their intelligence or how benign their intentions are.

(11) Seeing patterns where there is none is particularly well known, as this is how “conspiracy theorists” continually get explained away - it surely can’t be that people in positions of power would ever misuse it?! Seeing faces in clouds; finding significance to behaviour which was random; the “post hoc ergo propter hoc” fallacy (B happened after A, so B must have happened because of A, i.e. a pattern in time) – these are all ways in which our preference for discovering pattern - and therefore significance or agency - manifests itself.

There are good evolutionary explanations for why we have these biases. Economy of effort accounts for much of the above: thinking is expensive in terms of precious calories. Then there is the cost of being wrong: you are sitting on the African savanna 5000 years ago, and there’s a rustle in the grass behind you. It might be insignificant noise from the wind; or it might be a lion. If you think it’s a lion, and are wrong, it costs you almost nothing. If you think it’s the wind, and are wrong it could cost you everything. Which personality type is most likely to be selected for continuing the species? Those who are more apt to give it significance, to ascribe it to an agency – a mind; or the opposite? (We won’t get sidetracked into what this says about religion now)!

The flip side of wishful thinking is Hope, the last item in Pandora’s box. Not giving up when things look tough has obvious survival advantage.

Notice the repeated themes. All involve one or more of

wishful thinking;

jumping to conclusions;

reluctance to change our minds.

When we come across new information we integrate it into our mental model. We’re good at “rationalising” things we become aware of, to fit them in. If we cannot fit it in, then our default attitude is that it is wrong, not that there could be something wrong with our mental model.

5 Coping better with disagreement: thinking like a scientist!

The ideal way to cope with disagreements is for all parties to arrive at the truth! Needless to say, this is not always possible.

But how do we arrive at the truth? How do we overcome all these systematic faults in our cognition to arrive at the truth?

In society we have two mechanisms to help us achieve this: one is the courts; the other is SCIENCE.

For a subject that insists on precise definitions, “science” is a word that is surprisingly woolly in usage. It is, unfortunately, used both for a body of knowledge that was acquired with some difficulty, and for the methods involved in doing so - two completely different meanings … (not to mention the current fashion for using it as a synonym for “scientism” – treating science as a faith, a set of beliefs; or the actions taken by people who work in esoteric technical areas; increasingly people have been talking about science as if it is an institution).

I am not concerned with the body of knowledge here (or anything else) but the methods which make up science.

There used to be a convention in science (may still be, for all I know) that if you give an everyday word (e.g. “force”) a defined meaning, then you write it with a capital letter. So “Force” may be defined to mean a push or pull only, whilst “force” could mean “compel”.

So for the purposes of this article, I’m going to use “Science” (indicating that I have defined it) to mean the methods that an idealised (perfect) Scientist would use, not the everyday practices of people whose job is a “scientist” of some sort, who - in theory - have a modicum of training in thinking like a Scientist, but who are subject, like everyone else, to the usual systematic cognitive biases.

Children are taught in school about “The Scientific Method”, and there is some truth to this idealised way of thinking about science. But in reality science does not have to follow this pattern, and I’m confident I’ve read some scientists (like Albert Einstein and Richard Feynmann) saying that it usually doesn’t. Rather than “a method”, I think

Science is best thought of as a toolbag of techniques that we have picked up over the centuries for mitigating the systematic flaws in our cognition.

And we do not have to apply all the methods in that toolbag in any one project. We can do a perfectly good simple experiment that does not need to employ any sophisticated statistical maths for example. Even the sacred “experiment” let alone a “randomised, double-blinded, controlled trial” - whilst obviously essential tools to have in the bag - are not necessarily essential for a particular project. For example, I don’t think it would be right or helpful to claim that Robert Sapolski is not doing science, if all he is doing for a particular project is observing baboons, and recording their behaviour. Those two practices are elementary tools in the toolbag: recording is an obvious way to tackle the many flaws in our memory. “Observing” does not just mean passively watching, but searching for significance whilst doing so. That’s using the appropriate tools in the toolbag for the project at hand.

Defining terms is another simple technique from the bag characteristic of scientific thinking, that anyone can use.

What tools do we have in the Science toolbag to mitigate our tendency to think we are right and confidently “know” things that in fact we do not?

Here are two attitudes or practices that scientists employ for just that purpose.

1 Simply thinking in terms of hypotheses is very effective: starting by thinking of as many different ways that we can of explaining what we see, and trying not getting attached to any one of those, but examining them by designing an experiment which will transparently fairly choose between them, including ones which at first seem quite unlikely. (Somewhat akin to what Edward de Bono would call CAF - “consider all factors”).

2 Another tool is to be constantly assessing how confident we are that something is true. A typical experiment might go like this.

You are curious to answer a question; after a little research you devise an experiment to answer it; in designing it, you consider how your methods will maximise reliability and accuracy .

You take some measurements or make some observations, and as you do so you consider and record how reliable and accurate those measurements are. (E.g. “its length was 236 m +/- 0.5 m”). And given how accurate or not it is, with what precision should it be expressed?

You might make some calculations in which you would be thinking about whether they decrease or increase the error; and would it be correct to add or multiply (e.g.) those errors?

You might make a graph of those measurements, and as you do so you might show how reliable and accurate the data are with error bars.

You write a conclusion, and in it you say how reliable and accurate your conclusion is, after considering all you have done. An absolutely typical conclusion for a scientific experiment goes like this. “We found that X is true, with a probability of Y %, but more research is needed.”

When you practise this way of thinking over and over again, you get into the habit of

“tagging” all incoming information with an estimate of how reliable and accurate it is, as it comes in. If you learn this in school, and practise it for decades, it becomes second nature, just as counting in base 10 does, another entirely unnatural procedure.

And all conclusions are provisional, and expressed in terms of a numerical indication of how likely it is to be true. You are never completely 100% sure of something, there is always a finite - if sometimes negligibly small - doubt. In other words you train yourself away from the natural overconfidence and preference for certainty.

A great advantage of this way of thinking is that you are never wrong! You don’t have to change your mind from one position to another: all you do is adjust up or down your estimation of the probability that something is true in your thinking, as new information becomes available. This helps mitigate your attachment to the verity of an idea.

Doing that takes up more energy than the “Fast”, natural way of thinking which is to think “X is more likely, therefore X is true”. That is how we form a lot of beliefs. Thinking like a Scientist though, means forming an opinion of how likely it is, and noticing that: not “believing” at all, if “believe” means “to hold that something is (definitely, 100%) true”. We are liable - without training and practice - to assume that something is true if

it seems more likely;

it would seem to promise good things for your future;

you heard that version first;

“everybody else” seems to think that;

you’ve believed it for a long time;

you were in a trance (watching TV) when you were given a view, so were incapable of examining it;

you were told it by a confident, good-looking person with letters after their name. The truth is determined by awareness of the data, the facts - not who asserts it.

I think it is useful to have rather a strict interpretation of the word “science”. For example if everybody had a good grasp of the nature of Science on leaving school, then we would have insisted on a scientific trial of the covid “vaccines” before rolling them out, which never happened.

Corporations cannot do science. The core of Science is eliminating biases: corporations cannot get rid of the massive financial bias. They can do research, but not Science.

Your government spent a vast amount of your money on pharmaceuticals without any Scientific research into their safety or efficacy. (If that pharmaceutical turns out to do any damage, then you will be paying for that as well, after the deal your government struck “on your behalf”). Even without this strict interpretation of the word “science” there are plenty of people who understand that there should have been some proper independent testing; but an understanding that “science” means eliminating biases would make it easy and obvious to everyone.

6 Making Allowances for our Cognitive Deficiencies

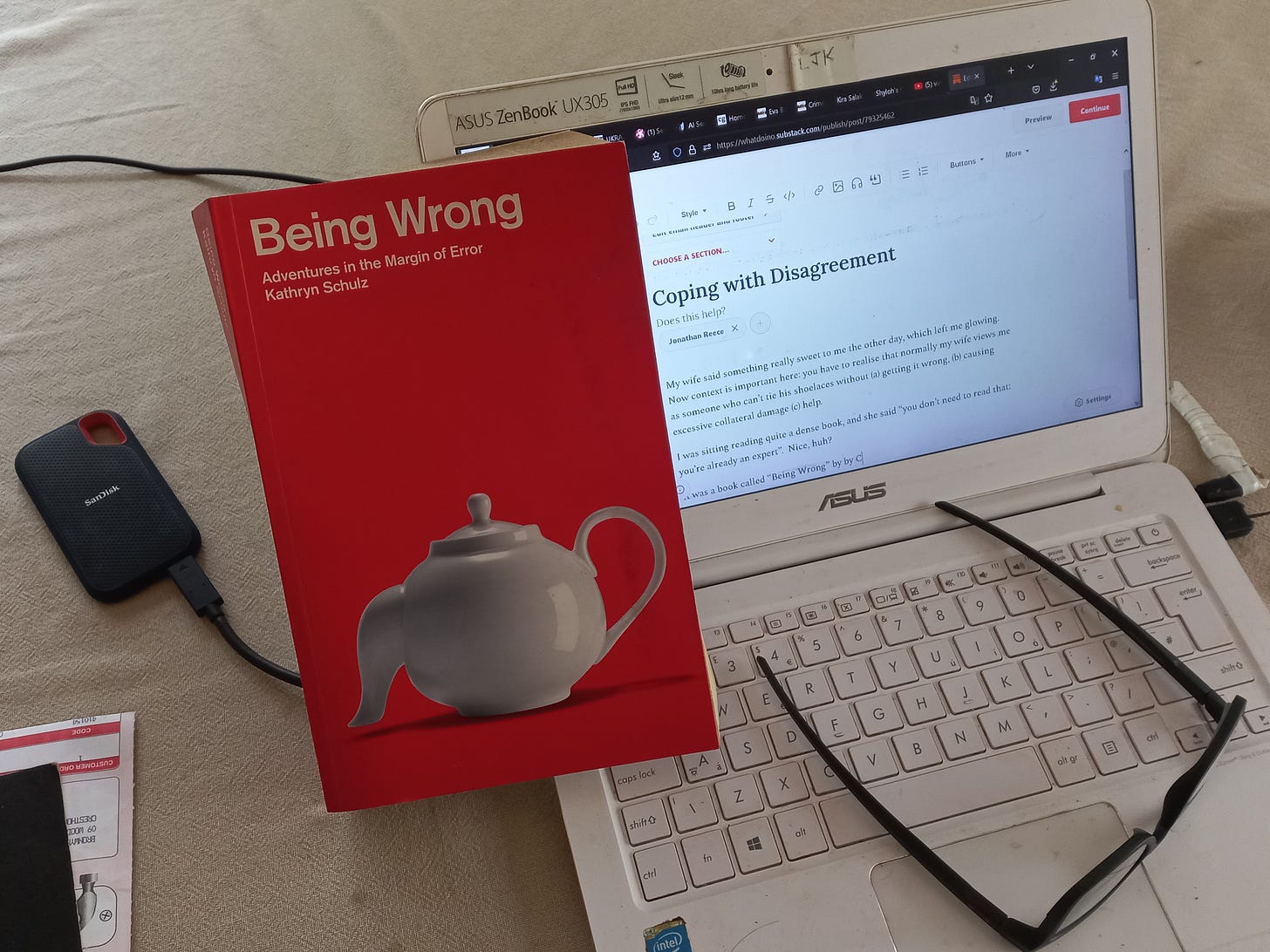

Consider this well known optical illusion.

Normally people perceive the upper horizontal line as slightly longer than the lower, when in fact they are the same length. (And it is because of a plethora of misjudgements like this that Scientists use another simple tool from the toolbag – measuring things). The next time you see this illusion, you will be forewarned to take care and make an adjustment to your initial impression. Once you are aware of this tendency, this bias, if you can recognise the situation, you can make allowance (compensate) for it.

In the same way, once you are aware of other cognitive biases, you can compensate for them, and take steps to avoid or mitigate them.

Consider how our experience with Joe illustrates OUR cognitive deficiencies!

We are surprised that he thinks differently from us (false consensus).

Because we are overconfident that we are correct, it follows that “he must be wrong”.

We rationalise that he is unaware of all the things that we know: we pay no heed to the things that he knows that we don’t. Daniel Kahneman, in “Thinking, Fast and Slow” calls this fault of humans [the acronym] “WYSIATI” - What You See Is All There Is – paying no or insufficient heed to the vast ocean of information of which we are ignorant, whose size and significance we just don’t notice. (Add this to the list of cognitive faults).

Our continued surprise that someone can think differently from us makes our rationalisation progress through that he is ignorant, then stupid, then bigotted, and eventually mad or malign.

We can improve our understanding or attitude by being aware ...

that we are all wrong all the time;

that everybody differs;

and that although our mental model is internally consistent, there are huge swathes of information of which we are ignorant that could upset the whole thing;

that we formed our opinion by giving preference to the first explanation that came along – not necessarily the best one. This is why it is so important for propagandists to give you an explanation as soon as possible. So on 9/11, immediately after planes flew into buildings, there were “experts” who just happed to be in the studios, mentioning the novel name “bin Laden”, when they could not possibly have known, if the event was a surprise to them. It’s why they would interview an ostensible random “man in the street” immediately after a building fell, who told you that the burning jet fuel softened the girders so that they collapsed … and why you pay no attention to the thousands of qualified architects and engineers who explain in detail why that is nowhere near possible.2

With training and practice, better reactions to ideas that don’t fit into our mental model could change from “they are obviously wrong” to things like

“that’s interesting: maybe she knows something I don’t, and I could learn something”!

“My view was just the first explanation I heard, so I must avoid putting too much credence in it.”

I would prefer it if there really were an effective vaccine, so I must watch out for wishful thinking, until there is proper evidence that it is effective or safe.

The plane flew into the building; later the building fell down. It might have been due to the plane - that seems the obvious conclusion; but perhaps (post hoc ergo propter hoc) I should give a moment’s attention to all those people saying they heard explosions, and those architects and engineers saying that it would take explosions to bring it down.

And so on … but this takes practice. And even scientists, who – in theory – have some training in thinking like this, are about as bad as everyone else.

7 A Pissed Homology?

At the end of the “experiment” I outlined above, there was a Conclusion. We express it giving an estimate of the probability of it being true. The Conclusion forms a very adequate epistemological model, readily understood, and - in theory - practised by scientists the world over.

Make an estimate of the probability of something being true, by examining how the conclusion is reached. Never ascribe 100% to it.

(The word “science” comes from the Latin for “to know”, whilst “epistemology” comes from the Greek for “to know”. Science is about how we know things in the sense of the practical steps we take to learn new things; whilst epistemology is about how we know things in the sense of the nature of our knowing; how well we know them).

Forget all that nonsense about “him speaking his truth”. There is only one truth, and that is reality as it is. People - of course - have different opinions about what the truth is. A better way to say it may be “he was speaking the truth as he saw it”.

Forget all that nonsense about parallel universes and alternative realities, that comes from a bad understanding of an unlikely explanation of something that nobody understands yet (although a few people have some techniques for understanding some aspects of it it under certain conditions).

Believing in thunder being caused by Thor’s hammer; astrology; “raising vibrations” (unless you can explain what is vibrating); “manifesting thoughts into reality”; alchemy … or any other fashionable magical thinking - may bring you the comfort of wishful thinking: but it does not have a good record of being right. Personally I would rather face up to reality, where things behave as they really do; where things make sense, even though we do not understand everything; where sometimes horrible things happen for no reason; where a positive mental attitude is an asset if it makes you get things done, rather than think they will happen because that is what you are thinking about; where self-discipline is needed. It’s your life: indulge away, if you think it will make you and others happy. For me, I think that in the long-term, facing reality and preparing for it by being as aware of it as possible is more rewarding.

A century ago people did have some grasp of this way of looking at knowledge: but instead of a continuous scale of probability of something being true, they talked about

hypotheses,

theories, and

laws;

a hypothesis being an idea for an explanation, without any evidence, necessarily; a theory is an explanation for something for which there is some evidence. A law is something that we have come to assume or be “certain” is true. So, in keeping with the times it was a hierarchical stratification rather than a continuum.

This way of thinking took a major hit when Relativity came along, and people realised to their horror that there were exceptional circumstances under which Isaac Newton’s Laws of Motion were wrong. Acceptance that an idea is wrong, and adoption of the replacement is often left to the next generation. (Did I mention that people are reluctant to change their minds)? There are still plenty of GPs (family doctors) for example, prescribing things that were known to be wrong decades ago.3

8 Changing Your Mind

Being wrong - no, discovering that you are wrong - is felt as a major “wake up call”. People who have changed their mind about something they have always held to be true almost invariably describe it as “waking up”, presumably because the most familiar experience we have of being unaware of things that (in retrospect) seem obvious, is being asleep.

Since changing your mind is difficult, I am impressed by people who change their minds – especially if it is as a result of examining facts that they have been reluctant to challenge. I will pay particular attention to them. It doesn’t - I hope it could go without saying now - mean that I am sure that they are correct! Thierry Vrain, Suzanne Humphries, John Campbell and Asseem Malhotra, spring to mind immediately; then there is Smedley Butler, John Stockwell, Norman Dodd, Richard Andrew Grove, Ted Gunderson, Joanne Nova, John F Kennedy, Catherine Austin-Fitz, Bret Weinstein, Tim Spector,4 Jim Macgregor and Gerry Docherty. I don’t know how many of these you are familiar with, but I think they are all worth your attention.

It’s so much easier to learn about something that you have no preconceptions about, that you know you know nothing about. Learning something new is much easier if it is just that, and not also having to recognise that what you previously believed is wrong!

It is easier to fool the people, than to convince them they have been fooled.

is a maxim usually attributed to Mark Twain.

9 Thinking like a Scientist - A: Thinking Hypothetically

Rationalising (in the sense of working out how to fit new facts into our previous understanding) is something we are good at, as we practise it all the time; it’s “Fast Thinking”. It’s how we make sense of the world naturally. It’s something that our ancestors have probably been doing for hundreds of thousands, or millions of years rather than thousands or tens of thousands. Changing our mind is something we are reluctant to do. And holding an idea provisionally, i.e. thinking hypothetically, is not something that comes naturally to us (Slow thinking), but something that can become second nature with practice: think of playing an instrument, or counting in base 10 when our natural way of counting seems to be “one, two, three, lots” as primitive tribes do. It’s amazing how good we get at thinking that does not come naturally to us, if we practise.

If you play chess or Go you inevitably get lots of practice at thinking provisionally, hypothetically. With chess that is all you do: “if this, and if that …”. Playing Go you do a lot of that, but have to keep switching to considering the big picture: such good training!

In theory everybody gets some science education. The quality of that education is very variable though. For example in three of the four science A-levels I took, I got virtually no training in thinking scientifically. I suspect the rarity of good education is widespread. I recently had a conversation with someone who would definitely consider themselves a professional scientist, who works with knowledge that few possess, and who has a science PhD. At one point they asked me “well if you don’t trust [some “authority”] or [some other “authoritative body”] who do you trust?” I hope didn’t show it, but I was appalled at this question coming from someone I had considered a scientist. It is great to know lots of arcane facts, but not having the basics is a huge handicap. It should be second nature to a “scientist” that the truth does not depend on who says it: you don’t “trust” (in that sense) anybody. To ask such a question is to make the ad hominem error, which is one that “we” were aware of thousands of years ago, and an error I imagine few educated people in the Middle Ages would have made. For the “scientist” I’m referring to, it meant that after these “authorities” had made some announcement, they couldn’t entertain any alternative. What they had been told skipped hypothesis and theory, and went straight to “established fact”.

10 Thinking like a Scientist - B: Curiosity

You may have heard some people saying that “the climate is cooling … I mean warming … I mean, er, changing”! And you may have heard that other people disagree. In that case – if you have any curiosity it might occur to you to wonder what the truth is … if you are adequately clear about what you know and what you don’t (a feature of Scientific thinking). I eventually got to that point, after retiring, and sat on the fence about the issue for months listening to both sides of the climate argument, even brushing up some maths and chemistry to try and follow the reasoning. Eventually I came to a conclusion (provisional of course – currently about 95%). I remember hearing with amusement in the wake of the “Climategate” emails, the glosses of the computer programmer (helpful “asides” to himself - comments written into the programme to make it easy for him to follow what he was doing). It sounds like he was struggling to write the programme to doctor the data, consistently lowering the older temperature estimates to make it appear to rise. What is certain is the quality of the data was appalling. (Look up the “Harry_read_me” files for more detail).

Whilst that question took me months - and I don’t blame anyone for not having the time or expertise to look into it – the question of whether the radio waves used by cellphones and towers cause any damage to health is dead easy! You can have an answer in 2 to 5 hours if you just have the curiosity and initiative to listen to people setting out the many papers demonstrating it. That’s an exercise almost anyone can do. Doing it would not only answer that question for you, but give someone without much experience of looking things up for themselves more confidence to do so in future.

Having the curiosity to look into things, and being prepared to think hypothetically (or being open-minded in more familiar parlance) means you do look into things. This is the sine qua non of science. If you look back at my description of a typical experiment, you see curiosity was the first thing. You don’t necessarily need sophisticated methods for answering questions; and if you have those sophisticated methods but don’t have the curiosity and open-mindedness, you don’t get started, like my scientist friend, who thought they knew the answer because they had been told something.

This also seems at least partly a character attribute as opposed to something that is trained, but I suspect there is scope for training. How curious are you about the world? How keen are you to learn about it? How interesting do you find it? You can have a school science practical changed into an experiment, by having your curiosity piqued first. Then an experiment is something you want to do, to answer your question.

I’m sad to say that education has, over the last century plus, moved away from genuine education and towards schooling. For what this means, who is responsible, why and how this happened, I recommend starting with John Taylor Gatto, his interviews with Richard Andrew Grove. Sitting being bored, and having no power to do anything about that, is liable to induce that “learned helplessness” (a feature of behaviour explored by psychologists in rats with electrified floors for a while, or fleas in a box). Initiative and curiosity are trained out of you. Look at some people famous for their achievements, and see how many of them didn’t attend much school, or educated themselves. Contrast that with the behaviour of the majority of people in response to being given non-sensical orders.

Children start with plenty of curiosity. If you have had children you will remember that demanding and stimulating phase when they discover asking “Why”! Scientists are people who don’t “grow up” in this respect, and maintain their curiosity. For an exemplar read Richard Feynman’s autobiographical “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!: Adventures of a Curious Character”. It’s inspiring as well as amusing and amazing.

Look at this product of research by King et al. 2021, July.5 (It’s a shame that they went along with the propagandists by using their jargon “vaccine hesitancy” for people who didn’t want the vaccine. I didn’t have the vaccine, but had no hesitancy whatsoever: I knew quite adequately why it was a bad idea. It probably helped get it published though).

One way of interpreting this might be to say that the longer one stays in education being told “think like this” the less one thinks for oneself. Getting out into a profession will allow you to regain some of your initiative (and by now there is considerable selection for capability to think); but you have to get as far as a PhD before you actually get any encouragement to think for yourself.

What “woke me up” was following where my curiosity took me – after I retired like so many others - so that I had the time to learn more about things I knew nothing about. It could have been any number of things, but in my case it started with “The Panama Deception”, John Stockwell, and “The Panama Connection”.

If a major event happens, like a “pandemic”, or 9/11, having the curiosity to look at it, to look into it, gives you the opportunity to spot the inconsistencies and lies. Without curiosity about the world, you will be less well equipped to cope with it.

I’ve been impressed how many people have seen through the response to covid. For me it was easier than for people who haven’t already had that “waking up” experience of discovering that you were wrong about a major feature of the World. Years ago I chose James Corbett as one of the journalist worth listening to, as – unlike most newspapers and news channels - everything he said he backed up with references, so you could see for yourself whether you agreed with him. He warned over a decade ago that “medical martial law” was coming.

11 Thinking like a Scientist - C: Thinking Sceptically

Consider Matthias Desmet’s analysis of his “mass formation” phenomenon. (Obviously I am not Matthias Desmet, so this is my - possibly flawed - interpretation of part of what he says). He says that in response to everyone being told e.g. that “there is a nasty new virus causing a pandemic”,

30% of people react “oh: there is a nasty new virus causing a pandemic”. At the opposite extreme

30% of people react “oh - that’s interesting. How do we know?” And the

remaining

40% think “uh-huh; how are other people reacting to this?

It seems to me that this could be the product of what might be regarded as one character trait. At one end of the extent of variation we have those for whom the fact that it has been said makes it true: let’s call them at the Suggestible end of the spectrum (not - for heaven’s sake - “gullible”)!

At the opposite end - let’s call it the Sceptical end – are people who want to know how sure we are of this: “how do we know this?" They want to find out the truth. As someone clearly at this end of the range, I would suggest … from my sample of one! … that my perception is that it is wanting to know the truth and how reliably we know it, not wanting to prove them wrong or even doubting them: “how well do we know this?” is my initial reaction.

For those not at either extremity on this scale, it may be that it is not this that determines the reaction, but other characteristics that predominate, like the strong desire everyone has to fit in with others. For these people it will be their perception of what “everybody thinks” that determines their (not necessarily very firm) reaction.

I think this conjecture - that people have a characteristic position on a Suggestible - Sceptical scale - is supported by this rather interesting Canadian opinion poll that you may remember from 2022 March (by Ekos)6. People were asked various question about what they thought about the Russia/Ukraine situation, AND how many mRNA injections for covid they had had. Here are four sample questions and an overall picture. (And it’s interesting to consider why someone chose this to investigate).

A quick overall summary of the results of this poll might be something like “those who agree with the image held up by the mainstream media on one issue (Russia being an aggressor who needs to be resisted by military aggression) are likely to agree with the image held up by the mainstream media on another issue - (everybody should get vaccinated). Conversely those who look elsewhere for their information disagree with those views, on the whole. That may be a character feature – some people are more suggestible than others (hypnotists say); but it could also simply be that they watch more television (and that might be due to some other personality feature, or simply chance or cultural milieu). So possibly – the more TV you watch, the more that dictates your views; or more contentiously – the less you think for yourself; or possibly - the more brainwashed you are.

Those who put their faith in mainstream media can look at this result and think “the conspiracy theorists are the gullible ones, whilst I am well informed.

Those who put their faith in other media can look at this result and think “the unquestioning masses are the gullible ones, whilst I am well informed.”

Each thinks that they are paying attention to “the science”. Unfortunately, I would contend that most people’s science education was so bad that they don’t really know what science is (although they think they do of course). A lot of them think they are paying attention to the science if they listen to what some third-party tells them what scientists are saying. Whereas in fact it’s not what politicians or TV pundits say that makes it right, nor even what a selection of “scientists” say that makes it right - IT’S THE DATA! If you don’t examine the data yourself, you are not paying attention to the science! A lot of people do not have the time, or inclination, or intelligence or knowledge … to do that easily. That’s fine … as long as they recognise that they do not “know”. All they know is that such-and-such person said … whatever. Jumping from that to “what they said is definitely (100 %) true”, is common practise (just look around); it’s what we do naturally; thinking “Fast”; and the opposite of a scientific approach i.e. the best techniques we have for determining the truth. (Here’s an example of someone who is way better than average at checking the data for himself).7

12 Thinking like a Scientist - D: The Pleasure of Being Wrong

Look at this picture of a parrot … or …

Is it a parrot?

When you see or understand things that you didn’t see or understand before, you get an “ahah!” reward in your brain. You have evolved to like understanding things. You will survive better in the evolutionary race if you make sense of your surroundings.

But what if that means you were wrong before? “Initially I thought it was a parrot”. As I mentioned at the beginning, people commonly do not like to discover that they were wrong – largely because of what they think others will think of them as a result, and exacerbated by their experience in school, where “being right” is elevated in importance. After leaving school most people need encouraging to go out and make mistakes. I think it’s no co-incidence that the second volume of Feynman’s autobiography is called

"What Do You Care What Other People Think? Further Adventures of a Curious Character”

Personally, I love to discover I’m wrong: for me that “ahah” reward outweighs fear of being thought stupid by others.

Personality characteristics and attitudes are to some extent inherited, but education, training, practice make a huge difference. They say that things you make a point of doing over weeks become habits; your habits, over the years, become your personality. So practising thinking “that’s interesting. How do we know?” can indeed become a bigger part of your disposition: and that would mean you have a more “scientific” attitude, and are more likely to arrive closer to the truth.

13 The alternative to stimulus – response

The Fast thinking that comes naturally to us seems to depend largely on the strength of connection between two concepts. Several things come to mind linked to a first idea. If there is an external stimulus, we get trained to prime several responses. But as humans we have the opportunity to engage our pre-frontal cortex and insert reason in between stimulus and response. Unfortunately, this happens less than we would like to believe"!

14 That is at its best!

All those systematic cognitive biases make us unreliable thinkers … and that is when we are at our best! In real life we are even less likely to engage in slow, energetic, rational thought! If you slept badly, or have had a demanding day physically, or mentally; or you are fearful, or angry or upset or drunk … rational thought is very unlikely to occur.

We have all just witnessed the effect of fear on a population. We are best adapted to living in the way we did for thousands of years – in tribes (of about 50 – 150 individuals: think Native Americans, or chimpanzee troups). The group, or tribe, has, it seems, evolved mechanisms for maximising survival.

When there is a threat to the group,

your best chance of surviving is to be part of the herd, not separated. So when we perceive a threat to the group, we have an atavistic urge to be part of it. (So lockdowns were used to make people feel separated. Preventing us from joining the group and making us feel isolated increases the fear; the increased fear strengthens the desire to be part of the herd. It was easy to see this self-reinforcing cycle of fear in some people).

It is best if there is a co-ordinated response by the tribe, so we are programmed by evolution to look to a leader. (So people were gulled by the most transparent lies by leaders).

… and to reject those who are not following the leader. (So people were hostile to and intolerant of those who were thinking for themselves).

This is what Matthias Desmet called Mass Formation.

Now (January 2023) - as fear of a pandemic must surely be fading - is the time when Joe Average has a chance of understanding, listening and thinking again. The propagandists will know this, and will soon produce the next stunt: war, financial collapse, another “pandemic”, destruction (blamed on terrorists) of data or communication, lockdowns in the name of “saving the planet” … There is plenty to choose from.

15 Recognising Science

Apart from the features I have already mentioned, it is helpful to be aware of the following features of Science, in order to recognise it in others, and to notice the absence of them in the propagandists claiming to “follow the science”.

Clear, succinct and accurate statements of logic and assumptions

Seeking facts to disprove ones own positions

Clear about gaps and weaknesses

Inviting challenge

16 The Effect of Intelligence

You might expect more intelligent people to make fewer mistakes. I suspect, though, they just make different mistakes, not fewer. I also suspect that the sort of mistakes that the more intelligent make are more dangerous ones.

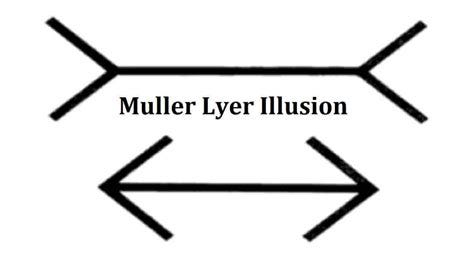

A favourite weapon wielded by armchair internet warriors is The Dunning Kruger Effect. This well-known piece of research is widely believed to show that really stupid people are too stupid to know how stupid they are. A lot of satisfaction seems to be gained by posting that such-and-such a person, who is clearly talking rubbish, is illustrating the Dunning-Kruger Effect!

The Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Dunning and Kruger concluded the following. The least capable people overestimated their ability [Blue arrow] to the extent that they thought they were above average – the 58th percentile, rather than the 12th which they actually were (which might be explained by Unjustified confidence; and optimism bias).

[Red arrow] They concluded that the most capable erred by thinking that others were more like them than they in fact were, so underestimated their own position in the group (false consensus).

I’ll come back to that. But - think about that most dangerous of our cognitive biases – the tendency to be overconfident of what we know. Who would you expect to suffer more from being sure they are right – the more or less intelligent? Think about it. What does their experience tell them?

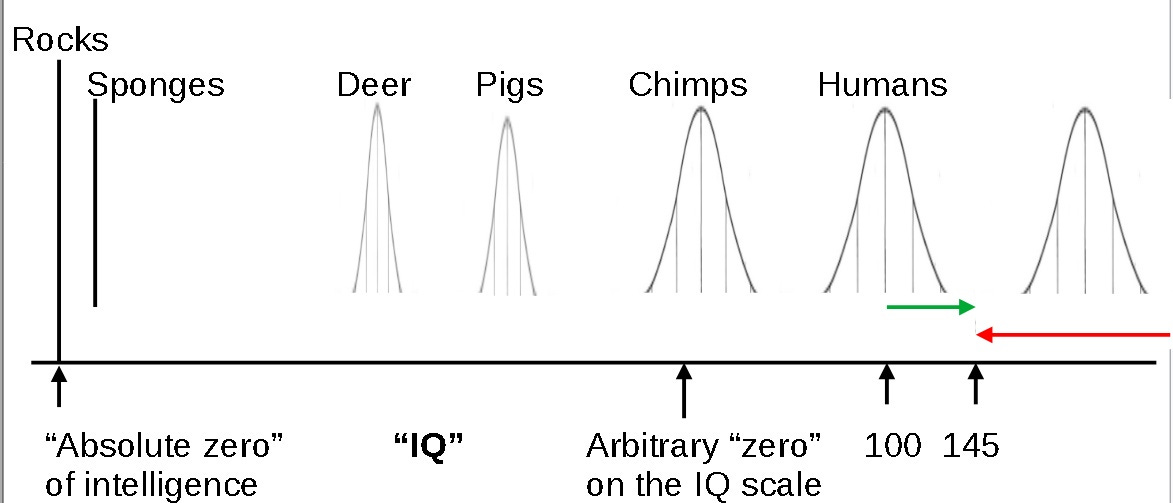

Let’s use IQ as a reasonable assessment of intelligence - (it has limitations, but it’s a helpful proxy) – people vary in a Normal distribution: most people are about average, and the further you move from the average the fewer people there are.

Someone like a doctor or teacher or priest would have done well in school. Even if the school didn’t give them an IQ test and tell them that they had an IQ of e.g. 130 (which might be common for one of those professions) they would soon know roughly where they came in the pecking order of ability - more intelligent than about 98% of people.

If you look at the IQ score in this diagram (the top line) it might strike you as coincidental that the average IQ happens to be exactly 100. That is because that is how IQ is defined: whatever the average currently is – that’s 100. That might prompt you to wonder how big the units are. Does an IQ of zero co-incide with zero intelligence, like that of a rock, for example? No – the units are simply a convenient size for dealing with the intelligence of people. They chose to allocate 15 points for 1 Standard Deviation (1σ, “1 sigma” – an indication of how wide the spread is). A sponge or a limpet is more intelligent than a rock, for example, but would certainly be a long way below zero on this scale.

Here is a diagram to illustrate what I mean, which is completely unscientific, unsourced, and unquantified – but I think it will make sense qualitatively to most people.

Such professions - (doctor or teacher or priest) - then go through their working life, and all day every day they spend knowing more than the people they talk to. Eventually these, it seems to me, are the sort of people who will be most susceptible to “knowing” that they are right, to overconfidence in their views.

It’s people who are sure they are right who are dangerous, as they are the ones who will be prepared to inflict their ideas on others.

Another – less flattering - way to say that all these systematic biases and flaws in our thinking are under-appreciated is that we are all much more stupid than we think!

An IQ of 130 is 2σ away from average. Consider someone with an IQ of 145 – or 3σ. They might go through life congratulating themselves on being more intelligent than 99.9% of people, which sounds impressive; but I would maintain that

the difference between high IQ people and the average person (green arrow) is insignificant compared to the difference between how bright they are and how bright they think they are (red arrow)!

(So that unlabelled distribution on the right represents how intelligent people feel themselves to be, since they overestimate how rational they are).

This is how there are people who have – not only the arrogance and the hubris – but the sheer stupidity to think that they should re-organise the whole World according to their ideas. The “elite” – or “Parasite class”, as I prefer to call them (since they are unlikely to be elite at anything and think they are clever for living at other people’s expense) - are planning on inflicting their ideas for a technocracy on the World. This is obviously going to be unpleasant for the new feudal class, but even for the Parasite class – I think the Law of Unintended Consequences will come back to bite them in a big way. Just imagine, for example, the effect on the population of getting rid of so many of the nice, empathetic people, and leaving only the corrupt, sneaky, greedy, selfish people, incapable of empathy (either genetically or from practice) and in a culture of aspiring to stealing from others as a modus vivendi, rather than having the self-esteem which comes from knowing that you are independently capable and competent. (If history is anything to go by, a lot of the lower echelon of that lot will be for an unexpected chop too).

I was once in hospital with a broken pelvis and knee after a fall from a rock, and the most salient part of the experience for me was learning that the doctors, nurses and cleaners there fell clearly into one of two groups on short acquaintance: either they saw you as part of the job, or as a person. Which group they were in made all the difference. I imagine that continued selection pressure over the thirty-odd years since may mean that the proportion of the two types has worsened. But just imagine this process on world-wide scale.

The doctors and other related professionals when the “time of trial” came, in the last couple of years, did about as badly (and well) as one would expect from history (assuming you know that doctors made up the largest professional contribution to the Nazi party, and nurses were happy to go along with the eugenic practices). Earning a living for your family is pretty high on your priorities; and as Upton Sinclair said - it’s hard to get a man to understand something when his income depends on his not doing so. Those who did best were the retired (whose income was not under threat); the remarkably principled – (hurray for all of them!); and those who felt thrown on their own resources, rather than part of a large organisation, e.g. Dr. Shankara Chetty, who had a large rural practice, with little help, and had to think for himself.

Oh, and – remember that Dunning-Kruger effect? It turns out that it is probably wrong! Two papers, by Dr. Ed Nuhfer and colleagues, argued that the Dunning-Kruger effect could be replicated by using random data. It seems the raised estimation for the less able, and the lowered estimation for the more able could just be stochastic artefacts. Try thinking of it like this: suppose someone knows they did really badly in a test. Perhaps they thought the test was going to be a week later and they had done literally no work for it; and they don’t know how many of the reasonable-sounding answers they had come up with from their experience had hit the mark. They might think that they could have scored anything from 0 to say 10%. Suppose their actual mark was 1%. Is their guess of how they did going to be too high or low? You can get a feel that the lower the actual score is, the more space above it there is and the less below it – even when you know you did badly. The lower the scored mark, therefore, the more likely the estimated score will be too high. Similarly at the top of the range. The Dunning-Kruger graph may be best explained as the score twisted towards the mean for the reason I’ve suggested, (below – blue line) then raised across the board due only to the optimism bias.

So the other effects used to explain the shape of the D-K graph – the unjustified confidence (on the part of the less able) and false consensus – they were just rationalisation (probably).

17 What am I saying? … and not?

I am suggesting, it turns out, that having a scientific attitude to knowledge is not only the best way of acquiring knowledge, but a good way of avoiding conflict over differences. It may turn out that such an approach may involve a bit of effort and practice! Well who would have thought it?

If your attitude when someone says something that you think is wrong is one of interest, rather than attack and defence, this is more pacific.

If your attitude to what you hold to be true is provisional and has a probability of being wrong that we try and assess; that we are wrong all the time and therefore modest, this also comes across better, as well as helping you to find the truth.

If you can discuss dispassionately the pros and con’s of two possible explanations, this might help … on the occasions when you are right ... to help the other adopt a similar disposition - and when you are wrong, to arrive at the truth yourself.

If you can provoke some curiosity in an antagonist about a peripheral topic, this might serve to prompt them to look into something related for themselves.

If you can spot the occasions when you are likely to suffer from wishful thinking, or

reluctance to change the first explanation that came along, you will be more ready to see things accurately and open-mindedly.

If both parties actually alight on the truth, then there is no disagreement. Great!

Now, science has an image of being difficult intellectually, and for sure, if you look, you can find some demanding mathematical techniques, and some knowledge that requires a great deal of prior knowledge to acquire. But the simple attitudes and techniques that I have mentioned in this article are fundamental to science, and the fundamentals are not difficult or beyond the capability of almost anybody. The most important tools in that toolbag are easy to use, and readily available.

I think the best way for attitudes and techniques like these to permeate society is to improve science education. Exercises where pupils are continually assessing accuracy and reliability are particularly useful. I am keen that people should view science as that toolbag of techniques for mitigating the effects of our cognitive biases; and should get some practice in using the techniques.

Since I have been talking about Science all the time in this article, as a way of coping with disagreement, it may sound as if I think people should be thinking like dispassionate scientists the whole time. NO! Science is only applicable when one is trying to arrive at the truth. This is actually a tiny proportion of the time. It is not the way you think when dancing, playing an instrument, climbing a mountain, making love, lying on your back watching the clouds, going for a run, doing yoga, shopping, caring for your elderly and young loved ones, laughing with friends … and on and on. Just adopt the best style of thinking for the occasion; and ...

Good luck!

Alexander Pope, 1711

http://www1.ae911truth.org/en/about-us

https://www.amazon.com/Lies-My-Doctor-Told-Second/dp/162860378X

5 Foods I got Wrong.

https://www.ekospolitics.com/index.php/2022/03/public-attitudes-to-ukraine-conflict-by-vaccine-acceptance