Everyday Carry for Survival

Be Prepared 4: What have I got in my pockets? How to maximise the efficiency of clothes. What a difference 4 bits of string & some binbags can make! Which 2 items are so important I tie them to me?!

Read this on Substack here.

Listen to it here.

For more articles like this, go to the homepage (click on the title - “What Do I No”) then the “Practical” tab - either read or listen

About this Article

This is part 4 in a series of articles on how to thrive if you have to sleep out of doors - whether that was scheduled or not. An unexpected overnight or two could be due to something as commonplace as a car breakdown, or something as extreme as rioters near your home e.g., when you might well want to "disappear" for a while. Being of “mature years” I’m just offering you some tips from my experience of making myself comfortable outdoors.

An increasingly large proportion of the World's population is cottoning on to the highly regrettable world-wide process in motion: so many people are putting more thought into planning for emergencies, and more people are contributing their thoughts. It doesn't matter if (like me) you think it is unlikely you will ever actually find yourself in this position: this is insurance. If UN soldiers are coming up the drive to tell me I need to go with them to emergency accommodation because there is some disaster taking place in the vicinity, I think it is likely that I shall want to go with them, not attempting a Rambo impersonation. But it doesn't do any harm to be prepared.

Today's main theme is ... How well can you do with nothing but what you wear/carry every day?

There is a large number of videos on YouTube with people going through the contents of their "bug-out bag", or "get-home bag". Rather than repeat information that is gone over many times by people with more experience than me in their particular expertise, I've given links to some outstanding videos (in "Be Prepared 1"), and I’m concentrating on aspects that I think are under-appreciated, neglected or unknown.

Ideally you will look at the first three in my series before this one, but it's not essential.

Be Prepared 1 A kit: Not surviving but thriving; unscheduled but not unplanned. [here]

the rationale for organising a kit

first-hand experiences of hypothermia;

links to some excellent videos on the topic and sub-topics.

Be Prepared 2 How to think about what to take [ here]

Alternatives to "The 10 C’s": Checklists and Mnemonics

My recent experience of having to fall back on my lightweight bag for months

Be Prepared 3 Travel Hygiene [here]

Why wash

How to wash

What with (two "secret weapons")

Unexpected benefits of practicing at home

Be Prepared 4 EDC for survival (This article)

How well can you do with nothing but what you carry every day?

Be Prepared 5 Lightweight kits (To come).

a grab bag

a lightweight backpack

options

Be Prepared 6 Longer term and extra options. (To come).

This episode runs counter to one of the main themes of this series: that you should not be aiming to survive, but to thrive. However, if you're stuck outside for a night or two, and really have nothing but what you normally wear or carry, then it could get serious quite quickly, even in a benign environment. This could well qualify as the proverbial "survival situation"!

Conditions can vary widely depending on where you are in the World: it would not be possible to cover everywhere. I'm going to talk about what is relevant for me, and you can adapt it to your circumstances. Ten years ago, when I realised that "medical martial law" was coming (i.e. the response to “covid") I chose to live somewhere where the climate is warm: the temperature here never gets as low as freezing, and on three or four occasions in the year it is mildly uncomfortably hot. But even here it would be easy to die of hypothermia if you have to be outside in the wind and rain unintentionally.

1 Concepts Introduction

1.1 Priorities

After keeping warm, priorities are drinking water, and getting adequate sleep. I feel that people who are thinking in terms of "survival" seem to underestimate the importance of sleep, and commonly think in terms of merely still being alive after a night or two. Without adequate sleep your decision-making and energy fall off quickly: you do stupid things - lose things, break things (including yourself). Your immune system suffers (as does every system of your body) and you get sick. You can quickly get into a vicious spiral of increasing lethargy.

You have to get busy looking after yourself; the easiest time to do things is straight away: you are only going to get more tired.

1.2 Who are the experts?

If you frequent the YouTube channels of people interested in this topic (as I have from time to time) you find various activities and skill sets that are relevant.

The military spend time sleeping outside; their kit tends to be robust and heavy, and mostly geared to shortish operations (unless they have external support).

There are people who walk short distances with a pack, to places where they have an activity for a day or so, like rock-climbing or bushcraft; weight is a factor that will have some consideration.

Then there are long distance backpackers, some of whom pare their pack weights incredibly low. These people have the experience to know just how much difference the weight you are carrying makes. If you are unfit or elderly, it's likely these people will have some relevant advice for you. But even if you are a male athlete, in the prime of life, and strong and fit from all the recent, relevant exercise you have done, the weight you are carrying will affect your performance considerably, so will be worth your consideration.

I put links to some outstanding examples of experts giving advice in Be Prepared 1. They are prepared with a back-pack of useful items: but here I'm mainly discussing no backpack - just what you have with you every day.

1.3 EDC

On-line there is another popular niche interest called "EDC", or Every-Day Carry. These people are connoisseurs of getting absolutely the finest version of things they carry every day, typically the ideal (for them) phone, wallet, watch, pen, holder for keys, pocket knife and/or multi-tool, first aid kit, charging cable, memory stick, screwdrivers and so on. In the US it commonly includes a hand-gun too.

I'm not discussing that either! I'm not reviewing items to find absolutely the best version of that item, but rather - simply considering which items you can carry to keep yourself warm, hydrated and well-slept, when you only have what you normally have on you. You can find ample videos explaining why torch X is absolutely the best.

1.4 Layers (of contingency not clothing)

If you pay attention to those with a military background, you find that they have layers of kit. These are people who are particularly likely to find themselves in adverse conditions; collectively they have a great deal of experience, and have given it a lot of thought. Each of them might have

a heavy rucksack, with everything they might need; but that may include

a lighter haversack for doing a patrol, so they can leave the rucksack at base-camp and move more quickly, with less wear-and-tear on their bodies;

after a fire-fight they may find themselves with just the kit carried in a chest rig or on their waist-belt;

finally they may be on the run with only what they have in their pockets.

Each of these "layers" of equipment is designed to cope with the same needs -

shelter

water

food

maintenance and repair

communications, and so on

... but subsequent layers gives increasing priority to cutting weight and bulk.

That is the particular needs of the soldier. But you should give some thought to various weights of kit as well.

So, the things you keep in a car can be heavier, if you don't have to carry them yourself much; but perhaps cheaper than your best equipment if they could get stolen if continuously kept there.

You should have a general lightweight bag that you can use in an emergency where you might have to carry it for some time.

There might be a collection of things to supplement that to suit the particular circumstances.

Consider having an even lighter grab-bag that you would use if you have to run, right now!

Another possible format for a survival kit is a jacket with lots of large pockets, by the front door.

... or a waist-bag ("bum-bag", "fanny-pack") that you take when out for a run or walk.

There are also things which are literally weightless - knowledge of your area, skills, experience, but also - as you will already know if you have been through the videos in Be Prepared 1 - food or equipment which you have cached (which will probably mean buried) in places where you might lurk on a route to a friend or relative's house e.g.

But that's mostly for another time. Today's layer is everyday carry - largely things you have in your pockets that you really would be prepared to keep about you most days.

2 Clothes

I'll get to the more appealing Bilbo Baggins question "what have I got in my pocket(s)?" soon; but first, in keeping with the technique for systematically assessing your kit that I outlined in Be Prepared 2, we start with clothes.

In writing some of this, I feel embarrassed to be having to state the obvious: forgive me; but my opinion of people who stock outdoor clothing shops is that they don't spend much time outdoors! I'm restricting myself to points I consider under-appreciated: I hope you find something you regard as a gem.

(Although this article's main theme is EDC - i.e. without a bag of kit - I'm only going to talk about clothes once in this series, so some of these comments will be more appropriate for an occasion when you have picked up your back-pack).

2.1 General Points about Clothing

2.1.1 If you’re going to be stuck outside unexpectedly, if nothing else, aim to have with you a layer more than you need in the daytime, perhaps a jumper tied round your waist if you are going about in shirt-sleeves. Having a jumper - or not - will make a big difference! It gets colder at night! Additionally, when you sleep you stop moving, when your muscles generate heat. That is why - when considering the components of your kit - your Shelter Kit is the same thing as your Sleep Kit: that's the time when you need the most shelter.

2.1.2 Wear practical clothes! (Or at least possess some! - and ideally have them with you, if you have to be dressed in a business suit or high heels). What does that mean?

Have shoes that you can walk a long distance in. It normally doesn't require military or leather boots, just comfortable shoes that won't fall apart. If it would be helpful to keep stones, burrs or ticks out of your shoes, socks or legs, consider having a pair of ankle gaiters: they take very little weight or space.

Wear clothes that dry quickly. This becomes very important when you are out for more than one day. Many people have heard that "cotton kills".

The less water your clothes retain, and the faster they dry, the sooner your clothes will be functioning well again.

If you are in a position to take off wet clothes at night, or wash them in the evening, then they can be dry by the morning.

Shirt, underpants and towel drying. Worn today; washed before supper; wear clean and dry tomorrow.

If you use such clothes on a day-to-day basis then in the long run you will save yourself time and money in laundry: less water to heat, and less tumble-drier time (if you are unfortunate enough to live in a place where you can't hang washing out to dry).

2.1.3 This is the MAIN POINT about clothes that I want to get across, to make clothing effective and efficient.

Layers of clothing are of two fundamental types: on the one hand insulation, and on the other, windproof (or somewhat so); and

Those layers need to be separable.

Each layer of clothes should specialise in doing one of those two things well.

An insulation layer, like a furry jumper - has big air spaces. If the structure minimises the fibres and maximises the air spaces, then it will insulate even when it is wet - whatever material it's made from. 1

Furry jumpers

Windproof layers by contrast are of thin, and tightly-woven material, like an ordinary shirt, or a waterproof jacket.

It's the combination of these two types of layer that is effective in keeping you warm - the thin, relatively wind-proof, and the thick fluffy. Alternate those two types of layer, starting with a fluffy layer next to the skin. That way the air is trapped in "boxes" - or relatively so: moist air can still diffuse through a shirt e.g.

Consider what a Norwegian might have worn a century ago. He might have a string vest (with plenty of holes for holding still air), then a shirt (thin material, relatively tightly woven); then a jumper (fluffy and airy), then a jacket - tightly woven to be wind-proof. Alternating types of layer: see? In very cold weather add another pair of layers - insulation then wind-proof.If you have separate, specialised layers like that, they dry quickly.

A"windproof" layers dries quickly because it is thin, and so absorbs little water, and everywhere is close to the surface; or in the case of waterproofs - absorbs NO water, just has it on the surface.

A furry, air storing, insulation layer dries quickly because the wind can blow through it easily.

If you fix both types into a single garment so that they cannot be separated, the wind cannot blow through it, and you get something which soaks up a lot of water and is slow to dry.

So I caution against these two popular choices

Consider the "puffy jacket" (or "down jacket"): it contains extreme versions of both these types of layer - the outer, very thin, relatively windproof layer, alternating with the inner, fluffy, air-trapping filling. The stuffing can be ultra-fluffy as it's unwoven since it is contained in the integral outer. This combination, is highly effective at keeping you warm - emphasising my point about alternating layers … BUT - IF the filling gets wet it sticks together. Since you cannot separate the two types of layer, the inside will only dry very slowly. This means trouble in the short term when it doesn't insulate; and trouble in the long-term when it gets mouldy due to the difficulty in keeping it aired.

I don't rule out a puffy jacket completely, if you are somewhere with a very dry climate, and you never suffer any allergies; or if you are backpacking for short periods between planned commercial laundry stops; but I recommend aiming to be able to wash all clothing by hand and have it dry overnight. It's that period when it's wet that does the damage, with bacteria and moulds growing. That wet period needs minimising. If you have to wear it wet, the warmth creates ideal conditions for growth of bacteria and fungi, like moulds.

(I dare say a lot of people will think I'm wrong about this. And to be sure, one of my many faults is that I tend to give excessive weight to the long-term over the short. I agree that mouldy puffy jackets (and sleeping bags) may not be a problem if you buy a new one every year). You can also reduce the wetting of the stuffing somewhat with products like Nikwax.

Fleeces are popular, as they do a convenient job of doing both rôles adequately - reducing the wind, and some insulating. But they are terrible when wet: Insulation is about zero as they are too closely woven, so that water fills the spaces completely, replacing all the air. Don't use a fleece! Replace it with an insulating layer and a windproof layer. Again - get clothing which does just one of those two rôles well.

[Hey - I've just found 1 other person who says get separate, specialised layers!]

2.1.4 You want clothes that cover you!

As a young man I used to take groups of people - often youngsters - out sailing and mountaineering. Often they would be in waterproofs borrowed from an institution. Sometimes that meant waterproofs were a bit on the large or small side. Those in waterproofs too large for them would be fine; but if your sleeves only reach your wrist, your hands are a large area exposed to wind and rain. It may not occur to people who spend almost all their time indoors that having exposed hands is significant, but the evaporative effect of the combination of wind-and-rain will be a big "heat sink" - a big drain on your energy.

Those 2 kids have just back-packed 60 miles across mid-Wales. Note sleeve!

Sleeves on jumpers should come down close to your knuckles, and have a turned-up couple of inches that can fold down to cover your hand completely. That is a very efficient way of keeping warm, without resorting to gloves - extra items of clothes to get lost, that you won't have with you, and which are not necessarily more convenient or effective. You can find pictures of Inuit with sleeves down to their knees. Sleeves on waterproofs should be a couple of inches longer than the layer below, so as to keep the rain off the sleeves of the jumper (despite the fact that those sleeves inevitably do get wet in the rain).Well-designed hoods will protect your face as well as the rest of your head.

2.1.5 Take trouble to adjust your clothing: make sure you're not too hot or cold.

As I said in "Be Prepared 3: Travel Hygiene", keeping comfortable in adverse conditions isn't so much a matter of being conversant with esoteric knowledge, but is largely a matter of taking a little trouble - just common-sense measures - to avoid problems. Take the trouble to be comfortably warm. If you are leaking energy rapidly, in the form of heat, then you will need to eat a lot of calories to replace it, and you will feel hungry. So make sure you are not leaking energy faster than you can help. Conversely, being slightly too hot will waste both energy and water. Take the trouble to do something about it ASAP.

When working in outdoor pursuits I learned that it's a mistake to ask people "are you warm enough?". They will invariably say "yes", as right then - although they may be leaking energy fast - they are not notably uncomfortably cold - not that they can't put up with; they don't want to whinge. They tend not to have enough experience to know that they could be more comfortable. Instead, ask them "are you comfortably warm"? Then you are more likely to get a more accurate assessment. If you want to check for yourself, get permission to feel their nose, up by the bony part, with the palm of your hand: if it's cold (due to vasoconstriction), they are burning fuel to keep warm.

[This is useful for babies too: feel their nose to check they are not cold; feel their ears for vasodilation, to see if they are too hot.]

Ask yourself the same question - "am I comfortably warm?", and if the honest answer is "no", then do something about it as soon as possible. Don't waste energy: it's in short supply.

2.1.6 Pockets

Although I'm happy for a waterproof jacket to have no pockets, if it's only used for rain, generally pockets are something you need lots of, and well designed. A problem that people have, who have not done much backpacking - one they don't realise that they have - is putting things down. We are so used to having smooth, clean, dry tables (or floors) to put things on, that we underestimate the problem of having somewhere to put things where they don't get lost, or dropped; keeping things clean, and dry. Your three weapons against this arepockets, preferably with zips - or at least a button - so that nothing falls out.

string to tie up like a washing line, to hang things on (whether they are drying or not); and to tether things to you!

a piece of cloth (could be a jacket, or poncho or dedicated tarpauline) to put things down on.

2.2 Specific Points about Clothing Items

Let's now consider actual items, starting with the extremities and working inwards to underwear. The things on your extremities are hats, gloves and shoes.

2.2.1 Hats

Hats are on the front line when it comes to protecting you from sun, rain and cold. Woolly hats and Booney hats are too obvious to need real discussion.

I keep a sun-visor - the sort of thing you might wear for playing tennis - at the top of my grab-bag, and use it often. It keeps the sun out of your eyes, off your spectacles or eye-protection, which improves visual acuity; it also affords your eyes a little protection if you are walking through thorny branches. If it's raining and you have your anorak hood up, then wearing a visor (or cap) will hold the front of the hood out in front of your eyes, so that it functions like the eaves of a house, cutting down water going down inside. It also means when you turn your head, the hood turns with it and you can see, instead of looking at the inside of your hood with one eye.

If you want to keep the sun out of your eyes, it's probably sunny; it is sunny, then it is often hot! If it's hot, then a visor will be cooler than a cap. It's just a cap without the top, so it will be lighter to carry, quicker to dry, and more versatile in ways you can modify it. If you are concerned about sunburn on top of your head, you can add a kerchief (bandana), held in place by the sun-visor. You can fold the kerchief small so that it looks like a cap; or leave parts hanging down at the sides to protect your ears, or unfold it completely and have the Lawrence of Arabia look - coming right down at the sides and back for more thorough protection from the sun, as is common in hot countries. You could use a larger scarf, or military-type scrim scarf ("sniper veil"), in a similar way; or as a makeshift miznefet - the Israeli military headgear, which is

essentially a voluminous piece of loose cloth or netting bundled somewhat, making a random asymmetrical shape (for camouflage and shade from the sun) sometimes nicknamed a bath-cap or chef's hat.

The sun-visor can replace the usual elastic-threaded rim.

The visor is the unusual thing, that you might not think of (which gives combinations with great sun-protection and camouflage potential) but of course I have the usual sort of things too. For everyday sun-protection just cheap wide-brimmed chinese-made hat from a cheap clothing chainstore is fine.

These are common in hot countries, with good ventilation:

A Tilley hat is a really well-made brand.

Here it was looking quite presentable over thirty years ago, but these days it looks a little more ... er ... characterful! I've waxed it heavily, so it's completely waterproof and it's what I wear to go for a walk in the rain. You can hear much better with this than with a hood; and it's great thorn protection.

2.2.2 Gloves

… I would not be carrying every day, but have a leather pair in my light rucksack. I probably would have sleeves on a jumper capable of covering my hands.

2.2.3 Footwear

I won't dwell on conventional advice about footwear ... but wear something sensible. The military have good reasons for wearing leather boots, but most people who do those long-distance paths for months at a time mostly wear trail shoes - essentially tougher versions of trainers.

Remember - we’re talking about what you happen to wearing on a random day when an emergency occurs, which may well not be what you would choose to wear for a hike.

If you don't lose them or break them, most things would be a lot better than nothing on your feet: most of us are not Cody Lundeen who goes around barefoot in horrendous conditions. But let's consider the pros and con's of some unconventional footwear.

Suppose you were wearing Crocs when you needed to disappear at short notice. They would be very comfortable, even without socks; and good insulation if you wanted to air your socks in the evening. Definitely not ideal if you have to walk over scree, or steep slippery mud, but if you have to wade a stream they would soon be keeping your feet warm again, since they would dry quickly because they absorb almost no water. They make great camp shoes to pack in your rucksack and change into in the evening while your main footwear (and feet) are airing, since they are extremely light. The soles would wear down quickly though, if you wore them for weeks. I did recently get a ... I think you'd call it a "heel bar" rather than a cobbler's - to stick more durable heels onto the bottom of a pair of Crocs. They seem fine after a few weeks, but we'll see.

Many times my main footwear for walking or running around in mountains has been what look like wellies, but are well-designed in Scandinavia for orienteering, which is popular there.

The brand used to be called "Nokia" when I started using them about forty years ago, and the model was aptly named "bogtrotters"; but when mobile phones came along they renamed the brand "Nokian" and the model - for some reason - "Trimmi". (I assume in Finland it means something appropriate). They are implausibly comfortable - for me at any rate.

They are not quite so robust as leather, so will wear out in fewer years; but being completely waterproof can have advantages; and the ability to slip them on or off instantly like slippers means that when you stop for a break you will take the opportunity to put your feet up and air your socks and boots.

I've used them for running over the Brecon Beacons, where the SAS train; picking my way through Dartmoor bogs; climbing mountains in snow in the Cairngorms; following paths indistinguishable from streams in the Lake District; sailing in dinghies and yachts ... (not to mention once windsurfing in a suit and tie and waterproofs!) and never had cause to regret it. I felt particularly grateful for having discovered them, when lots of British squaddies came back from the Falklands conflict with trench-foot. (In fact, come to think of it, I confess to having forgotten to take them off when I came in from the garden, and am currently sitting at this desk in them - and very comfortable they are too)! I have two pairs - one is quite new, and the other pair is the one I mostly wear, which after a decade or so developed some minor splits, but are still very functional for most uses.

After getting the insides wet in a river they will dry more quickly than trainers or trail shoes, and be less smelly. Hang them upside-down to dry: the air containing the newly evaporated water will be cooled, and will sink down out of the boot, to be replaced by drier air.

It would be a lot better than nothing to be wearing "jellies" - those sandals made from tough plastic (I guess polyurethane). After all, the Romans achieved quite a bit in sandals (and thick woollen socks).

They are heavier than Crocs for camp shoes, and provide less protection and insulation, but they will last many times more miles. (One strap, where your big toe is attached, breaks after about a week; thereafter they are fine for years). Again, they dry almost instantly since they absorb zero water. Clearly they wouldn’t be one’s first choice for hiking, but remember - we’re talking about what you happen to have on when disaster stikes. If pressed I would confess to having done some long hikes in the Drakensberg in them. I would certainly rather have them on than flip-flops (slip-slops): I never wear those.

2.2.4 Waterproof Jacket

I would find it hard not to get irritated by shops selling waterproofs ... if I were not of such singularly calm, beneficent, and philosophical disposition. ;-)

I consider the jacket in this photo well-designed. I bought it (30 years ago) from an army surplus store rather than a commercial shop - surprise surprise! (The army do actually go outside - unlike the pox-ridden gormless cretins of commercial manufacturers and "outdoor adventure shops". ... And breathe)!

This jacket was no longer completely waterproof when I bought it: the army get rid of clothes which have some function left, despite being worn past a good standard for people going outside. In this case a few months of pounding around under a heavy pack had rendered the Goretex membrane leaky over the shoulders. Nevertheless, despite having some newer, completely waterproof Goretex jackets, this is one of my favourites - AS IT IS DESIGNED WELL. (I've improved the waterproofing somewhat by waxing it, but this doesn't work so well as it does on a cotton jacket). This one has a short zip to allow access to chest pockets on inside garments, but otherwise no gimmicks; no lining; no pockets; an ordinary zip (not a waterproof one) which runs from your nose to close to your knees, opens from either top or bottom, with a flap from each side over it; just medium weight Goretex material with a minimum of seams. But it would function well on the foredeck of a yacht with waves breaking over you; canoeing in changeable weather; bird-watching; sitting in a stalled ski-lift at minus 20 degrees Celsius; walking into storm-force wind and rain; or hitch-hiking: (I've checked it in all of those). I suspect if a manufacturer actually made such simple jackets commercially, in a variety of colours - which they could do for a reasonable price - they would sell like hot cakes.

Again, it's about covering yourself. Hoods should come well forward of the face, long enough to cover and wrap over the peak of a cap; and should attach at the bottom of the collar, a collar which comes up to your nose. Then If you are walking into wind and rain, lowering your head only slightly will prevent the rain from hitting your face and from running down inside the jacket. The collar should be loose enough to wear plenty underneath. Sleeves should come about to your outstretched finger-tips; (you can always fold them up). The front zip should open completely, i.e. go all the way to the bottom so as to allow maximum temperature adjustment. (You may be using them as windproofs rather than waterproofs). And there's a lot to be said for the jacket coming down to close to the knee, so that you can use leggings rather than waterproof trousers (more anon), and safely sit on it. It should have no lining attached (see above - all that stuff about separate layers). If it is mainly to be used in rain, it should be light as you are carrying it most of the time.

Good luck finding a good waterproof jacket. I hope that I have at least given some help in what to look for!

You don't have to be as fussy as me, though: any waterproofs are better than none. The cheap ones you buy in builders' merchants with PVC on the outside have a lot to recommend them. I keep a set in the car. An ultralight backpacker wouldn't consider them for a second, but they really would keep the water out - much better than my old Goretex army-surplus jacket - and that's really what you want when it's bucketing with rain. The waterproof that makes it into my lightweight backpack is an army-style poncho: terrible in the wind, but fine in the wooded valleys around me.

2.2.5 Waterproof trousers

... are subjected to a lot of abrasion. Your legs will rub them together when you walk; you sit on rocks; they are likely to brush past thorny plants; so expensive Goretex trousers (and I do have a couple of pairs) don't stay waterproof long (if you use them, that is)! But - if your jacket isn't designed with looking cool on a trip all the way to the car in mind) but is of a decent length, then you can make do with waterproof leggings instead of trousers.

I made a pair for almost no cost from some cheap waterproof material from a garden shop/builders' merchant. It is a simple matter to fold it into a tube for each leg, cut for length up to your crotch on the inside leg, and the hip on the outside. There is no sewing, just stuck together with duct tape on each side of the “seam”, and a loop of duct tape at the top to fix each to your belt. The strong, slippery, slick material copes well with thorns: they tend to just slide over. Despite the robustness of the material, the pair weighs exactly the same as my very lightweight Goretex trousers, as they omit the top section covering your pelvis. Since they are open top and bottom, the warm moist air tends to move up through them, especially when you walk, so they are much better than waterproof trousers at avoiding condensation inside. They are completely waterproof. They go fine with a poncho.

But whether you go for leggings or waterproof trousers, have some! Being completely covered makes a huge difference to what you can do, and how long you can do it for. (See the incidents in "Be Prepared 1").

2.2.6 Jumpers

I did once find some jumpers designed for practicality. Would you believe it - it was also in an army surplus store! These may not be to your taste, unless you happen to be "sartorially challenged" like me, but they are practical. They open top to bottom for maximum thermal variation; they have a neck which can zip right up to your chin; large zipped pockets; and the German army make every conceivable size variation. I was even able to find some to fit my ridiculously long arms. The Germans get them made by Helly Hansen, a Norwegian company. These ones are 80% wool and 20% nylon. I would probably prefer 100% man-made fibre; but if I'm going to be camping or expecting rain, I'll give it a bit of a rub with a piece of beeswax.

Polartec Alpha material

If you are feeling wealthy, buy or make a couple of jackets with"Alpha Direct". (That's the name of this material). Somebody (scientists working for the US military) has finally worked out how to make really airy, furry material - which saves me from having to learn to crochet, as I once started doing when I was about twenty, in an effort to make some efficient insulation.

2.2.7 Trousers (US - “pants”) and shirts

Many people have heard the saying “cotton kills”. Poly-cotton is the way to go for trousers and shirts: i.e. the fibres are a mixture of 65% polyester (very hydrophobic and quick-drying) and just 35% cotton (for strength, grip, and more forgiving humidity management).

Note the pockets, with closures!

Polyamide trousers and shirts are marketed as even faster drying, but they are not so hard-wearing, are more flammable, and tend to be uncomfortable due to the humidity. They often have vents to help with the humidity problem, which then make them more subject to tearing.

Trousers need to have plenty of pockets if you are going to have the wherewithal to make yourself comfortable: two at the back, two at the front and two "cargo" pockets on the thigh. I've mostly used the (UK) brand called "Craghoppers" for a long time (for shirts as well) even though the trousers lack a second cargo pocket.

The one they have is big enough to cope with what I want to carry, but - [Craghoppers are you listening?] - they would be more efficient with the weight distributed between two legs. They are very well made, though; have a lifetime guarantee, and as you would expect, last well. The material is the right weight for a compromise between being hard-wearing and drying quickly.

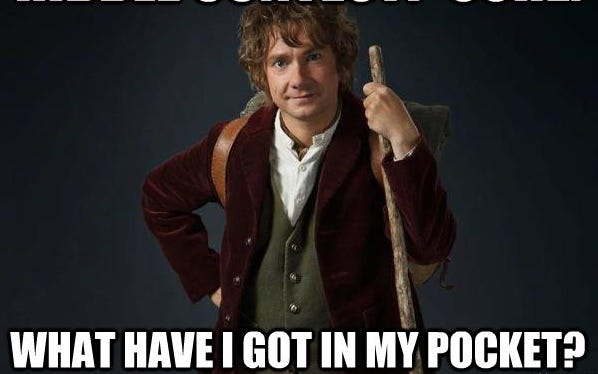

2.2.8 Windshirt

You can buy windshirts which stop the wind more effectively than an ordinary shirt, which are therefore good as an outer layer.

These things bundle up so small I keep one in the pocket of my jumper. The pair make a very effective combination.

2.2.9 Underwear

I would suggest that poly-cotton boxer shorts are best, whether for men or women. They ventilate the area better than tighter underpants, and are easily washed and dried.

For the most efficient underwear from the thermal consideration, look at what the Norwegians wear: either fibre-pile (furry material, see jumper in above pictures) or string (net) vests and long-johns.

Combine string underwear with a shell-suit (thin, light, windproof top and bottom, and you have two extra layers that will pack into a very small volume, like a little waist bag ("fanny pack", "bum bag") and you have the means to cover yourself all over with very efficient insulation. You might take it on a run or walk if you were going to be somewhat isolated.

Here is a very small leather bum-bag I sometimes wear to go for runs in more remote places.

Since it's so small it contains a pair of tights rather than the full "string long-johns"; and I don't possess shell suit trousers. If you had to sit out some bad weather, or twisted an ankle badly, you can wrap up in an "emergency blanket". You can see the contents:

long-sleeved vest,

wind-shirt,

long buff,

a pair of tights,

2 bin-bags (or an "emergency blanket") to cover yourself completely if it's raining;

2 candles with a lighter (will supply warmth for several hours held under the bin-bag over your head; or make it easy to start a fire in the rain);

knife, whistle.

In this picture you see the same equipment rolled up in the windshirt to wear around your waist ... except now with proper long-johns instead of tights; and yet, it's lighter (because there's no bag) and wraps closely to your body without bouncing around. (The rubber bands - or a piece of cord - are necessary since the wind-shirt has such slippery material it would come unrolled).

3 What to Carry

This is what I have in my pockets, whilst trying not to look particularly bulgy. Using the system outlined in "Be Prepared 2", and starting with the little finger ... "knife, light, lighter" ...

3.1 Tools

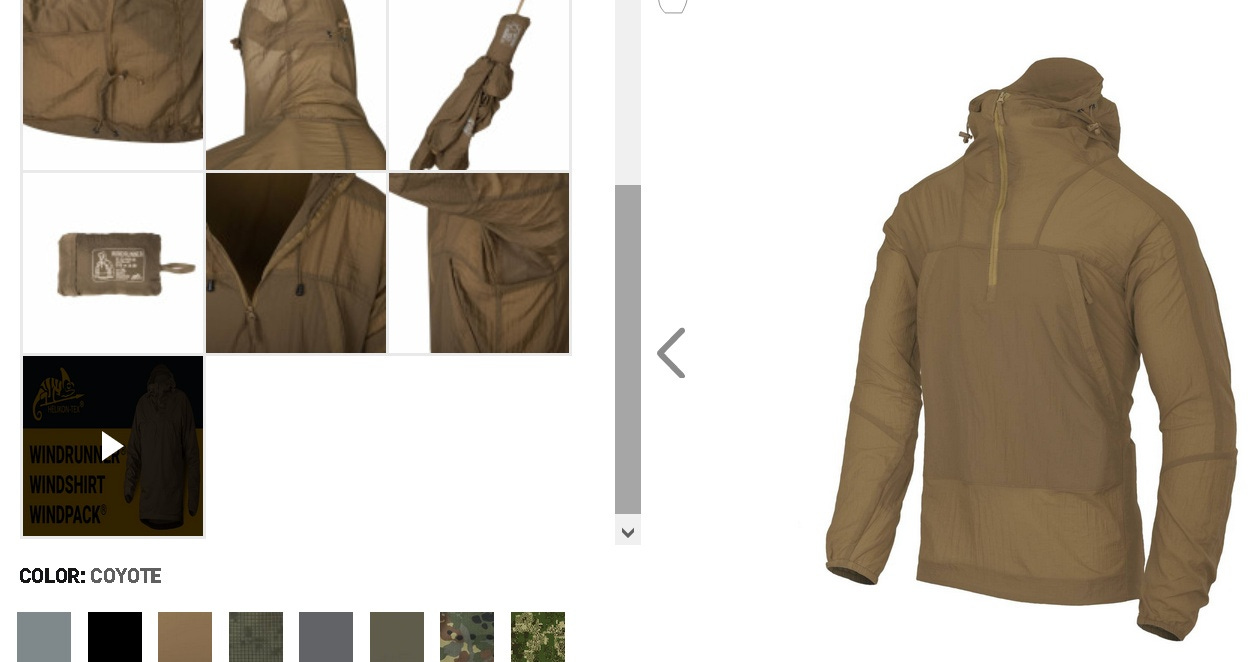

3.1.1 Knife

Now, most people, when considering what they would like in a survival situation, seem to come down in favour of a very robust sheath-knife.

These certainly have the advantage of being extremely durable: you don't want it to fail.

But the weight penalty is high, and socially it's problematic carrying such a thing on your belt, to the extent of being illegal in some places, if you cannot justify needing it for an immediate use.

The reality is that I do not carry one every day – very rarely in fact - so I cannot expect to have one on me in an emergency. Remember we're talking about what you actually have on you every day rather than what you would like in a back-pack.

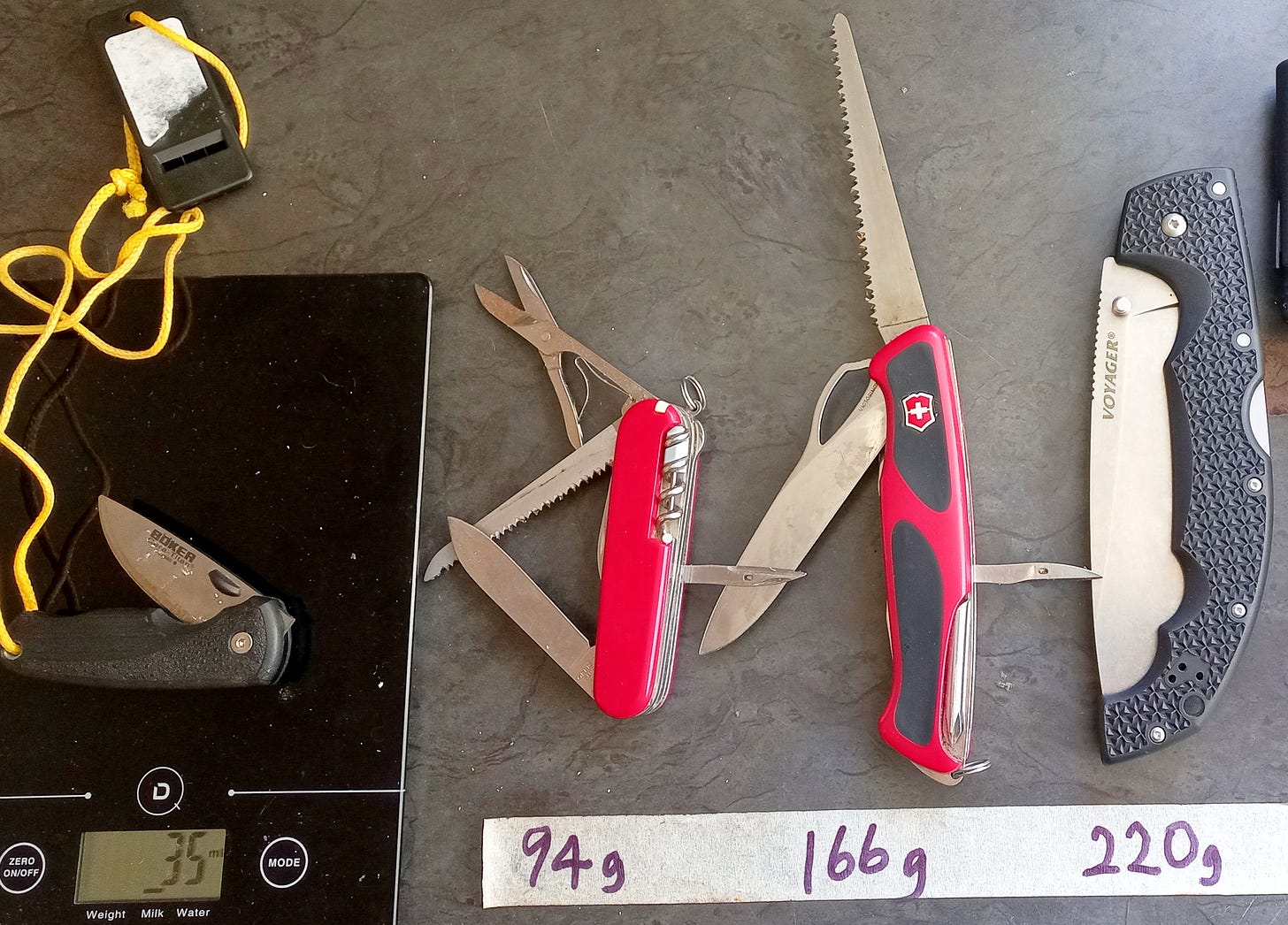

In the UK or traveling I would have a common-or-garden Swiss Army knife on me (e.g. this Fieldmaster), which complies with the law in the UK and most European countries. Although I've lost one or two in my nearly seven decades, I've never broken one. The essentials are the blade and saw; and the awl and scissors can be useful too. In the circumstances we are considering, you would probably use the saw more than the blade, despite the blade being more versatile. This would be quite sufficient if it’s all you have on you. The best person for showing just what you can do with this little knife is Felix Immler. It’s an easy carry at about 95 g.

At this moment, the version I have in my pocket is the slightly larger Swiss Army knife (a Ranger 78 M Grip), 166g, as many days I use it to prune trees in the garden. (Lots of our trees are leguminous and are there to build extra nitrogen in the soil, by simple "chop and drop").

If you just had one knife on you in an emergency, this is exactly the one I would hope to have on me. It's tied to me so that I can't lose it!

(That snap shackle allows me to detach it easily from the tether if I have to reach higher than the tether would reach. You'd get such a thing from a chandler; but a lark's head would allow you to do the same a little more slowly, without the weight and cost penalty).

However, if I also had my little Leatherman Juice multi-tool with its saw on me (see later), then, rather to my surprise, I've become a fan of what initially struck me as a ridiculously large folder - a Cold Steel (the brand) Voyager (the model) XL (the size) drop point (the blade shape). (See above, on the right).

In the wooded valleys around me thorny creepers and brambles are most easily dealt with using a machete, and the Voyager XL functions very well as a (genuinely) pocket-sized, folding machete. With two and a half fingers around the very end of the handle, and a string loop around the other two fingers it swings well, with the belly of the blade a good 21 cm (8 1/4 ") from your nearest knuckle. You'd be surprised how good a grip you have of it like that. A purist might complain that you should use a folding knife for slicing or cutting and never for impact. However, given the flexibility of what I'm cutting through, and the extremely robust design of this particular model's joint, in practice I haven't had any problems, and don't anticipate any. It’s much easier to deal with spiky things by slashing at them from a distance.

It would work very well for batoning too, always with the blade half-open2. (If you're not familiar with batoning, it's splitting a log by putting the edge of the knife on the end of the log, and hitting the knife into it using a thick stick as a mallet on the spine). Perhaps I'm particularly dopey, but I don't really notice the weight in my pocket either. Here’s someone with considerable experience of knives enthusing about his, which is almost identical except for the blade shape.

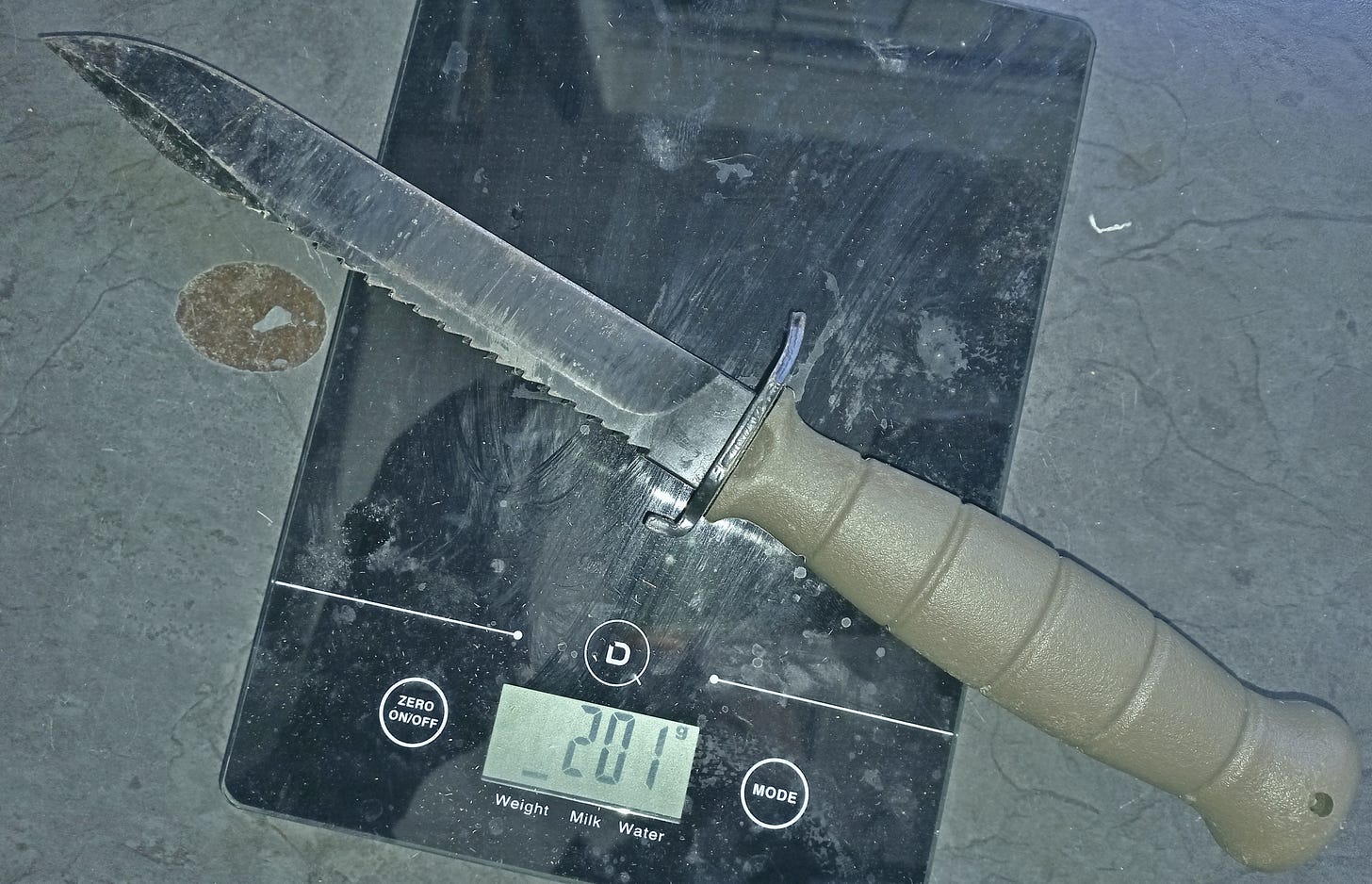

If I were in a colder or wetter country, where splitting wood for a fire was going to be significant, the knife I'd hope to have on me would be the Glock Field knife (78 or 81 - with or without a saw-back).

For splitting wood efficiently using a batoning technique length is important. (The cross-section area of a log increases with the square of the diameter your knife will cope with: in other words a little extra length makes a big difference to the efficiency in getting through reasonable-sized logs). The Glock is peerless in terms of length for the weight. I challenge anyone to find a robust, commercially made knife close to this one's blade length of 6.5", 165 mm, that only weighs 201g (7.1 oz). It's light because the distance from the cutting edge to the spine is small, as it was originally designed to double as a bayonette, so needs to be small (top to bottom) for effective stabby penetration; but it's quite a thick blade, so it's robust. That small distance from spine to edge also means it's a larger-angled wedge that you are knocking into the wood - better at splitting, like the difference between an axe designed for cutting, and a splitting maul.

A purist might complain that it's not a full tang knife (where the metal continues right to the end of the handle). But polyamide (the handle) is as strong is some respects as steel, and in practice the difference for almost all tasks is nil. You can find videos on YouTube of people demonstrating just how tough it is by using it as a chisel, with a mallet, to break concrete bricks ... not to mention firing guns at it! It's tough!

3.1.2 Light

It's helpful to have a small torch for emergencies. Twice I've bought expensive tiny torches which recharge their lithium batteries with a USB lead, and twice had them fail electronically. It was probably damage from a power surge. Nowadays, the tiny torch with button batteries that lives in my pocket has never failed. It cost about three dollars at a gas station. I put a plastic disc over one end of the battery so that it doesn't run down in case it gets turned on accidentally in my pocket.

[Edit: I’ve recently splashed out on a little Rovyvon torch (flashlight) for my keyring. They seem remarkably tough, have a great range of brightnesses, and haven’t failed after a year. The Missus hasn’t broken hers either!]

3.1.3 Lighter

Of course the aim is to be able to be comfortably warm without having to light a fire, since

it's a big tax on time and energy;

it advertises your location widely (smoke, flame, smell, strong signal for night vision devices; and

if you want to rejoin society inconspicuously, you will smell much more strongly of woodsmoke to others than you do to yourself.

In addition to a mini-Bic lighter, with some duct tape around it (it burns well) I have a piece of fat wood, a cerium rod and a scraper.

In a lighter the cerium rod is usually called a "flint", due, presumably, to a misunderstanding of how a flint and steel works. Actually the flint rock is hard and scrapes off a piece of the cerium metal, which burns, not the other way around. Really, you replace the “cerium” in a lighter, not the “flint”. And whilst we're being clear-thinking - never "pedantic", please! - let's call it a "cerium" rod, not a "ferro" rod, if you want to abbreviate it! In 1903, when Auer invented an alloy that was better at making a spark than iron, by mixing iron and newly discovered cerium, it was, indeed, appropriate to call it "ferrocerium"; but now the main constituent is cerium, only 20% iron, and also contains small amounts of magnesium, lanthanum, neodymium (the stuff powerful magnets are made of) and so on.

Fat-wood is resinous wood from the base of the branches of dead fur trees. When a tree opts to shed lower, ineffective limbs, it recovers the resin that it expended so much energy making, which stops the dead branch being an avenue for the entry of bacteria and fungi. Fat-wood can be scraped to form tinder (a spark will catch it alight), or shaved to form kindling (catches fire quickly from tinder, but unlike tinder, burns long enough to catch fuel on fire).

These little items are wrapped (together with a small compass) in a buff to keep them together, and from rattling in a front trouser pocket. I see that I had a small bottle of ethanol when I took this picture, too. Not only is that good for lighting fires in the rain, but can be used for sterilizing your skin as well, e.g. after relieving yourself without the opportunity to wash your hands. I recently swapped that in favour of a lighter-weight tub of insect-repellent (which also burns well, of course).

There's also a Fresnel lens in my wallet (for focusing the sun to light a fire).

3.2 Food and Water (ring finger)

You will recall that the three priorities I mentioned at the start were keeping warm, keeping hydrated, and sleep. Without some sort of bag I do not carry food (with the occasional exception of a protein bar). I have, however, cached (buried) some resources in directions I would be likely to be going if on foot; and keep some in the car. (See the videos in Be Prepared 1).

In my other front trouser pocket is the other item which is important enough to tie to me, like the knife: a water-filter.

Sawyer Squeeze

Nowadays you can buy ridiculously cheap filters which will reliably remove any bacteria, protozoa or parasites in water, and, if you take the trouble to backwash each time you use it (listen to me - every time!) and don't let water freeze in it, it will continue to work indefinitely. Sawyer have a good reputation. I keep a Sawyer Mini in a trouser pocket all the time, and a Sawyer Squeeze (above, only slightly larger, and comes with a lifetime guarantee) in my pack.

Sawyer Mini

Ah! I see they have listened to criticism, and started making a version of the Mini that will take a water (or soda) bottle screwed on at both ends, not just one. So now you can use a clean water bottle to backwash it, rather than the syringe they supply (an extra item to carry). Without this I am in the habit of "blowing" the last mouthful of clean water back through it with my mouth. After use, back at home, you can back-wash it with ethanol, or mouthwash, or vodka or dilute disinfectant, to stop any mould or bacterial growth, as water will only dry very slowly.

The great thing about these filters is that they contain a single layer (like a collander), with holes of accurate and uniform size. As long as you send some water back through it each time, you can remove particles (bacteria e.g.) blocking the holes. (Imagine putting a collander with pea fragments stuck in holes, upside down under a running tap). Then it really should last for decades at least, as they have done in African villages, when one person is trained how to use it rigorously for the whole village.

You can use it as a straw to drink unsterilised water. Discard the first mouthful - consider it rinsing any possible moulds out. And if you don’t have means of squirting clean water back through it, “Blow” the last clean mouthful back the way it came.

It will not remove any dissolved substances: so it will not remove salt from sea-water; some areas of the world have unwholesome amounts of arsenic in the groundwater; nor any dissolved pollutants from factories or housing. But - given a reasonably natural environment - you will be safe from bacteria, bilharzia, giardia, cryptosporidium and so on.

If you are in an area where you are dubious about solutes, then you can use a filter such as a "Lifestraw" which includes a carbon filter stage, but which has a limited life, and is larger. (Or in a pack, an even larger version is a Grayl).

The pictures above show Sawyer filters screwed onto a plastic water-bottle. The Mini is slightly narrower and fits into a pocket almost as easily as a pen-knife.

(As well as a little duct tape around it - always useful) mine has a bootlace tied to it with several turns (US "wraps") so that I can tether it to my belt, to be sure not to lose it. It also functions to catch drips of dirty water. If you fill a container (e.g. a pop bottle) with water from a stream, screw it to the filter, then hold it up with the filter at the bottom (as you inevitably do) then it’s possible for drips of dirty water on the outside of the bottle or container to run down onto the outside of the filter, and down into whatever you're catching the clean water in. The turns of slightly fluffy cord prevent this.

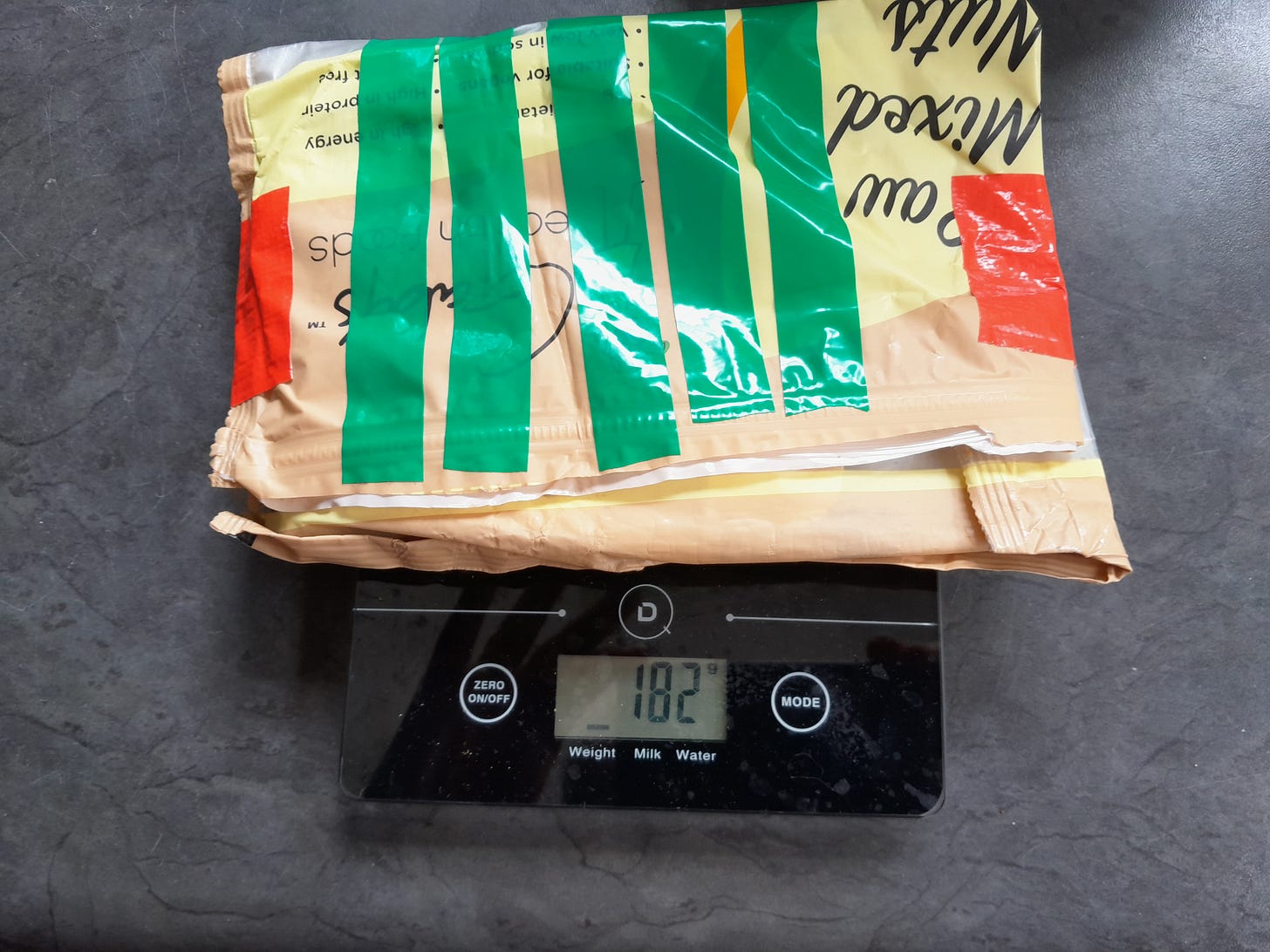

In a cargo pocket I carry a sachet designed to hold food and to fold flat but to stand up when it's full.

In the absence of a stream, as long as you have some container to collect water in, then you can use a cloth to soak up dew, wring it out into the container, then use your filter to drink it.

3.3 Shelter and Sleep (middle finger)

3.3.1 Keeping Warm

You can store any number of small useful items in pockets or small pouches, including an emergency blanket ("space blanket" - plastic coated aluminium foil) which does well at wind and water-proofing; but insulation necessarily takes up a lot of room. How on Earth do you cope with that?

3.3.1.1 The extra clothes you have:

Another layer: if you're walking around in a shirt and jumper, carry a jacket for example. If you're walking around in a shirt, jumper and jacket, stuff some neck-to-toe underwear in a little pouch.

In the same front pocket as my knife is the fire-lighting kit wrapped in a buff, which will go on the head;

and in a back pocket is a second buff - neatly folded, thin, merino wool - that can go over the neck and as much face as needed.

In with the cordage in the head-net is a pair of tights, they take so little room. The head-net will also keep you warmer (and stop you losing so much water overnight, since you will be partly re-breathing the humid air you exhaled).

One cargo pocket: Black tights in the centre of the photo, wrapped in a piece of spare cordage, keeping it secure and tidy.

(Wrapping it is not such a good idea if you are short of room, as it makes it more rigid in shape. It conforms better to the space available if it is loose. This is an example of the general principle that it's a bad idea to stuff stuff-sacks until they are rigid, for the same reason).

I don't know about nowadays, but fifty-odd years ago, when I was growing up near 42 Commando Royal Marines, I gathered that it was common for marines doing exercises on Dartmoor in the wind and rain, and getting cold and miserable, to wear a pair of women's nylon tights under their trousers - for purely practical reasons, you understand! They absorb zero water, and form that all-important dry layer immediately next to the skin, even if subsequent layers are wet.

3.3.1.2 Improvise a mattress and a duvet: You can keep four bin-bags in your pocket.

Contents of a cargo pocket. L to R: container, space blanket, water sachet, mylar pouch, bin bags (2 clear, 2 black).

In the country you can normally find dried grass or fallen leaves - anything like that - commonly called "duff": you stuff that into the bin bags (remembering that it will compress, so add plenty). You tape the open ends of a pair of stuffed bin bags together, and use one pair as a mattress and the other as a duvet. Even if it is damp it works surprisingly well, in my experience, as long as you have enough underneath you.3.3.1.3 Use a space blanket and extra cordage to fashion an A-shaped roof to keep rain off. (Make a ridge line, and attach a piece of cord to each corner of the space blanket, by wrapping a large pinch of sand in the corner, and put a slip-knot around it). Waterproof shelter is harder to improvise than insulation. Protect it from the wind and sharp things. Once it breaks it’s nearly useless, and that’s very easy to do.

So in one cargo pocket there's thin plastic of various shapes: I have

a food-grade plastic sachet, (closeable) (once contained raw mixed nuts, I see);

... with duct tape and PVC tape stuck on it; containing

the sachet I mentioned earlier for water (making two possible water containers),

four bin-bags and

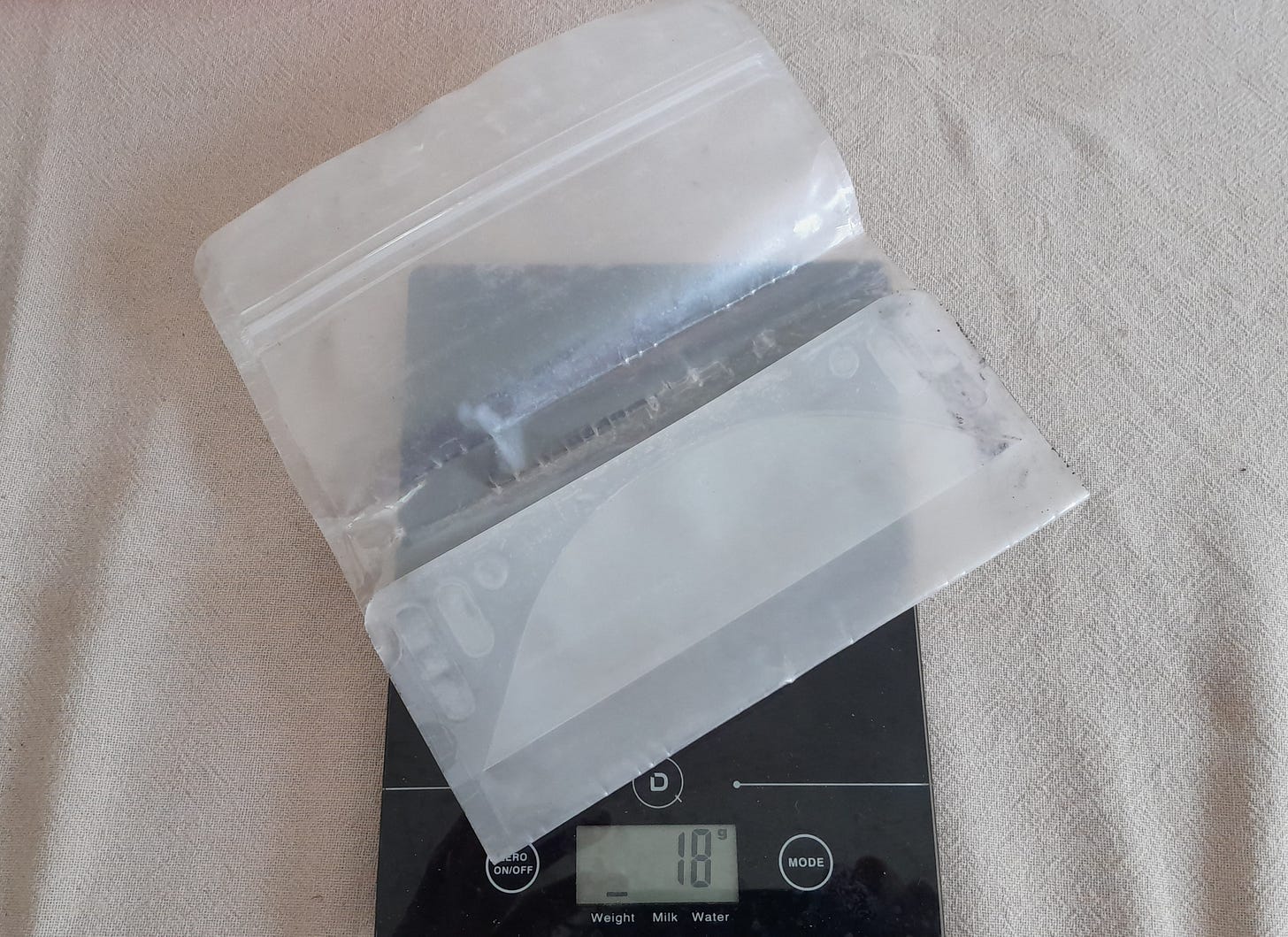

a "space blanket" or "emergency blanket".

There is another mylar pouch (or two) that will take a phone. It will keep it dry - particularly if I really do not want to be located, and therefore jettison my phone at an early opportunity. However, it is probably sufficient to take the battery out3 and put it in two Mylar bags. I've done a simple test, and that seems effective enough for most circumstances. (Even without the battery in, they have a capacitor so that it doesn't lose information when the battery is taken out, and can still be operated remotely by the powers-that-be)!

3.3.1.4 Using a fire

As I explained above, using a fire has big disadvantages: aim to be functioning comfortably without one. But if you do want to use a fire, you can make it less conspicuous and more efficient with a Dakota firehole.

There are various ways you can improve the efficiency of transfer of heat from fire to yourself. If you only experience the radiative heat, almost all the energy is wasted up into the air.warm some rocks (not from a stream bed) in the fire, then use them as hot water bottles, or heat them more and bury lots of them in the ground underneath you (if you are lying on the ground).

heat a metal cup of water (or a discarded tin can).

Warm your hands on it;

put it between your thighs, by your femoral arteries;

inhale the steam (exhaling away from it so as not to cool it unnecessarily;

drinking hot water is very effective;

fill a discarded pop bottle and put it inside your clothes.

The heating of that cup/can can be made more efficient by improvising a tramp stove from another tin can.

If you have a walking staff, and it’s an aluminium tube (cheap, light, strong, works well) you can put the bottom end beyond the fire and on a rock, so use the fire to heat the air in the pipe. Hot air will rise through the pipe, and you can fill your clothes or a bin bag over your head with it.

3.3.2 ... And Off the Ground

Ok, so you have a mattress, a duvet, and a roof: it's also preferable to be up off the ground. If you are going to be hanging around for any length of time you will appreciate somewhere to sit too.

With some cordage in your other cargo pocket you can improvise. A quick and simple arrangement, needing very little to carry, is a deck-chair configuration.

3.3.2.1 Make two poles by using your saw (knife if necessary) to cut down two saplings, and trim branches off, and cut the length to the height from the ground to what you can reach with a raised hand. Using the little saw on my Leatherman juice (about the same size as the UK-legal Swiss Army Knife) this took me about 120 seconds for each sapling, assuming you want to be quiet and saw all the way through rather than snap them. In these photographs I was experimenting with how thin a sapling you can get away with. The thinner one you can see was pushing it further than ideal, especially with one pole bending a little more than the other; nevertheless it was functional.

3.3.2.2 You need a piece of cordage to lash one end of each pole to a tree-trunk, at about chest height. Alternatively (as in this photo) put the cord over a higher branch to hang the pole ends from. This is a little less stable than lashing them directly to the trunk (one pole can slide up a bit and the other down), but if you you want to take it down quickly, it's a three second task. It's also easier to adjust the angle of the your improvised recliner. It also means that if your tree is too narrow, the poles can swing apart to accommodate your shoulders. You need a minimum 4 m (13 feet) of cordage for that job (depending on the size of your tree). To minimise space taken up in a pocket I use thin but strong cordage for this task. Brand names include Dyneema, and Amsteel, but the generic name is UHMWPE, or Ultra High Molecular Weight Poly-Ethene. It's very slippery material, but that doesn't matter for this job. You could also use appropriately thin and strong braided fishing-line.

Close-up of seat section

3.3.2.3 At a height that's convenient for sitting, make a seat by taking a second piece of cordage and go backwards and forwards from pole to pole. It's best to go around the poles in a figure-of-eight pattern rather than round and round, otherwise one set of strands will be higher than the other, and you would be putting more weight on the top strands. To stop it from slipping down the poles when you wriggle, you can put a turn around each pole (as in photo), or even an overhand knot, although I haven’t found the latter necessary. Now you have a seat. I found the cordage like paracord (kernmantle construction) but with just a single central strand (rather than the more common seven inner strands), to be a good compromise. It has plenty of friction to hold still on the poles, but doesn't take up much room in the pocket. My cord was 8 m (26 feet) long, which is about a minimum; but it was enough to avoid it digging in.

You may be able to tell that the top strands of the seat section are looser than lower ones, in order to make the seat more level.

3.3.2.4 So that you can recline back in a deck-chair-like manner, you now need to continue up the poles for your back and head to rest on. With a large proportion of your weight on the seat section, and some on the ground where your feet are, and the remaining weight of your upper body spread out over a large length, you can get away with much finer material. You can go the high-tech route, but I've found that dental floss is quite adequate for this emergency expedient! It's very cheap; you can buy rolls of 100 yards (91 m) rolled neatly onto a spool which takes very little room in the pocket, and one will do the job.

I carry two such spools, removed from the hard container, to save space, in a fold of duct tape to stop it from unrolling. You could also use Kevlar thread, or fine, braided fishing line: these would be stronger, with better friction, and better camouflage; but more expensive, and you may need to spend a considerable time making a neat spool, as such long, fine material would be hard to stop tangling if you made the sort of hank that tidies the other cordage.

Head-net contents: deck-chair kit on the right - 2 cords and floss.

One cargo pocket contents

3.3.2.5 Finally you need to put something to raise the front of your feet, or dig a slope to keep your feet at right-angles to your legs, otherwise you will find your ankles will need extensive warming up in the morning in order to be able to stand and walk (particularly the Achilles tendons).

To be sure, it will compare unfavourably with your bed at home for comfort for a whole night's sleep, but compared to sleeping on the ground you will be much less likely to be bitten by ants, ticks, snakes and so on. The itching from bites of mosquitos, ticks, spiders and ants (not to mention scorpions) will not kill you, but if it stops you sleeping, that can escalate into a serious problem. That is why I keep this collection of cordage in a mosquito head-net. The rest of your body can be pretty well covered by clothes. The net needs to be held away from your head to stop mosquitos biting you through it, so If you don't have a boony cap you can fashion a hoop with several turns from something twiggy and flexible.

You will be able to get some decent sleep with the appropriate mindset.

3.4 Maintenance and repair (of kit and self) (Index finger)

In the same front pocket as the water filter I have a large bandana which could be used as a bandage or tourniquet. In order to get the size, material and colour I wanted, I simply went to a haberdashers, bought a piece of cloth and had it hemmed.

There are some pieces of duct tape wrapped around various things. (See Josh's videos for how to use this to improvise stitches for large gashes, in Be Prepared 1).

Bottle of alcohol for sterilising skin. Squeezing a jet of water/alcohol from a bottle is very useful for removing small bits of dirt from grazes or cuts effectively and painlessly, so that they don't go septic. (This was the most commonly used item in my First Aid kit when taking groups out mountaineering)!

In with the cordage in the head-net is a tiny tube of superglue,

2 needles and thread in a sealed plastic straw,4 and

a tampon or two. (Did you know that tampons were originally invented for treating bullet wounds? What a curious comment on the human race, that we are only sufficiently motivated to make so much innovation by warfare)! (Photos later).

and some Disprin (for pain or clots), and usually an antihistamine.

3.5 Information: navigation & communication (thumb)

I keep a wallet in a back pocket, with some money, cards, and a paper list of phone numbers.

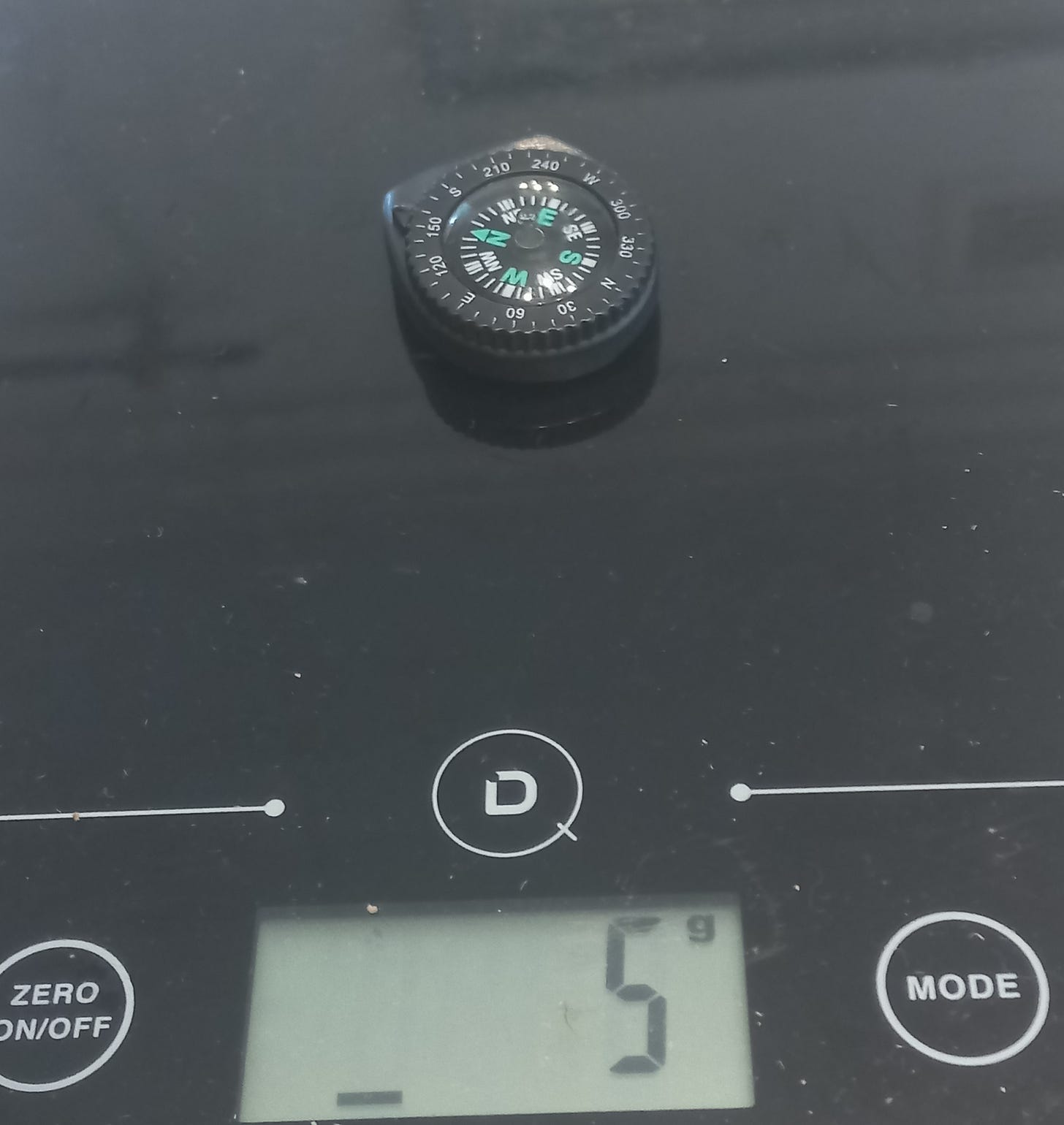

Wrapped in the buff with the fire-lighting material there’s also a compass;

that's a Suunto one designed to go on a watchstrap. I would put it on a watchstrap if I needed it, but I've stopped leaving it permanently on my watchstrap, as I've twice had the experience of the clip breaking after a couple of years, and losing the compass. A pity, as it was handy when, somewhere unfamiliar, the GPS would tell me to start, with "head South-West"!

I have a watch, with a solar panel on the face, and

my keys which have a SAK classic on. Instead of a toothpick I have a second pair of tweezers, which I've filed to a narrow point for removing ticks e.g.

3.6 Defense and concealment (fist)

I'm not qualified to give any sort of advice about self-defense, and think it would be unwise to do so. ( ... Unlike almost any other topic that I'm unqualified in, when I'm very happy to pontificate)! I grew up in the UK where almost nobody has legal guns. Nowadays I prefer not to have a gun as it necessitates being on a list of people with guns. In a country with relatively few people owning guns that makes you a target if there are any corrupt police who would tell criminals where to find guns.

In woodland, with a knife (or, better, a saw) you can make a decent staff or spear which could be used in some circumstances for self-defense.

I'm unlikely to have anything in my everyday clothes that would assist in camouflage or concealment, although the mosquito head-net makes a white face stand out a lot less. You could make your bandana from camo pattern material. If it is unusually cold I might take a scrim scarf (sniper's veil) which would make adding vegetation easy.

BUT you could also put in some preparation in a particular location to aid in concealment. Here are some examples of what is possible.

So, as night draws in in the woods, and it starts to feel colder there's quite a lot to put on: the tights go under your trousers; your spare jumper goes on; a woollen buff covers your neck and lower face, with a second buff on your head, overlapping with the lower one; over that goes a mosquito head-net. There's a mattress of sorts underneath you, and a duvet of sorts on top, and a small waterproof roof.

With a bit of effort and determination, you can keep yourself warm, watered and slept for a few days, with nothing but what you have in your pockets and a spare jumper with you.

And for the "sartorially challenged", or those who don't obsess about their looks, it doesn't really look too bulky or outlandish, does it? ... and there are a couple more items in my pockets which are not relevant here.

4 There's more?!

Well, that's a look at what you can do with literally nothing but your everyday clothes; but I use a handbag. I call it a "handbag" (US - "purse") because everyone

knows how you behave with a handbag: when you are out, you keep it close to you at all times; you hold it (or sling it over a shoulder) when you're walking. At home, you know where it is: it's somewhere convenient to grab when you go out. I have just one item to grab when going out. Mine is usually in the same room as me, and I'll explain why.

I'm very bad at noticing when I haven't drunk enough water. I can hardly perceive thirst at all. I have to remember to drink at intervals; so the main thing I have in my handbag is a bottle of water. If I'm walking around with a heavy bottle, that helps to prompt me to reduce its weight by drinking from it!

That's a common enough thing for people to keep in a handbag - a little bottle of water.

The other thing that helped prompt me to start using a handbag was reviewing the many scientific papers pointing out that being close to a cell-phone or cell-phone tower is bad for your health. That's a very easy thing to do, and if you aren't aware of it, and maybe rationalise that government would never introduce measures that would harm people, take a look. If you are adept at internet searches you could satisfy yourself very thoroughly in four or five hours. (If you're still using the mainstream media - Google in this case - it will probably take you rather longer).

Since the intensity of the radiation drops off with the square of the distance from the source, putting a little distance between you and your phone makes a big difference. I was an early adopter of smart phones, and had one in my trouser pocket for many years while I was working. In the pocket the phone might be say 2 mm from your flesh; in a hand bag ... let's estimate that its around 6 cm from you: that's 30 times further away; but the intensity of the radiation is 30 x 30 times - 900 times weaker.

Or let's say that the distance from your testicles or ovaries is important. That might only double when putting into a handbag that you are carrying, which would reduce the intensity of the radiation by four times ... if you are carrying it around: but a lot of the time you are sitting somewhere, and if your phone is not in your pocket but in a handbag located a metre or two away, that's a considerable difference.

Anyway, those are the two factors which prompted me to change my behaviour and start using a handbag.

The one I use is made by Helikon-Tex and they call it "essential kitbag" (although my memory is that they called it an "essentials bag" when I bought it several years ago).

(I have a spare one as it’s important to me)

As you can see in this photo, it's basically a canteen holder: so if "handbag" doesn't sound macho enough to suit you, call it a "canteen pouch" ... or even (for maximum machismo at the expense of accuracy) an "ammo pouch".

I have several products made by Helikon-Tex,5 and have always been very impressed with their build quality, robustness and remarkably thoughtful design. After at least 6 years I had to replace a zip on the side pocket that I use several times a day.

The back has "molle" webbing, so instead of the shoulder strap you could put it on your waist belt for a time. In addition to the obvious pouches on either side, it has small pockets on the front, back, interior and lid. My phone goes in one side-pocket,

with little else so that it's easy to get in and out. (The other side pocket is more filled, but still not a jig-saw puzzle to get it in; see later).

Contents of one side-pocket.

In the main compartment goes an absorbent cloth (i.e. towel - see "Be Prepared 3" ) then the flat lid, then the canteen cup, and into that goes the canteen. With the cup already in there, it’s easy to get the canteen in and out .

Contents of main compartment

(The silicone rubber bands are round the canteen to make handling easier if it contains hot water. I bought them from Amazon: they are intended for chefs to put around things in ovens, I believe). The canteen and cup fit in comfortably. Since I carry it around a lot, weight is at a premium for all the contents, so I splashed out on a titanium canteen, which is much lighter than steel, and doesn't have the long-term toxicity problem of aluminium. Since the canteen is unlikely to fall out I have replaced the draw-string around the rim with a couple of stout zip-ties (cable ties) which may be useful sometime, and make the rim more rigid, so easier to get stuff in and out. Since I want the bottle of water, I might as well have the canteen cup, and lid, which take up very little extra room (obviously the canteen nests in the cup).

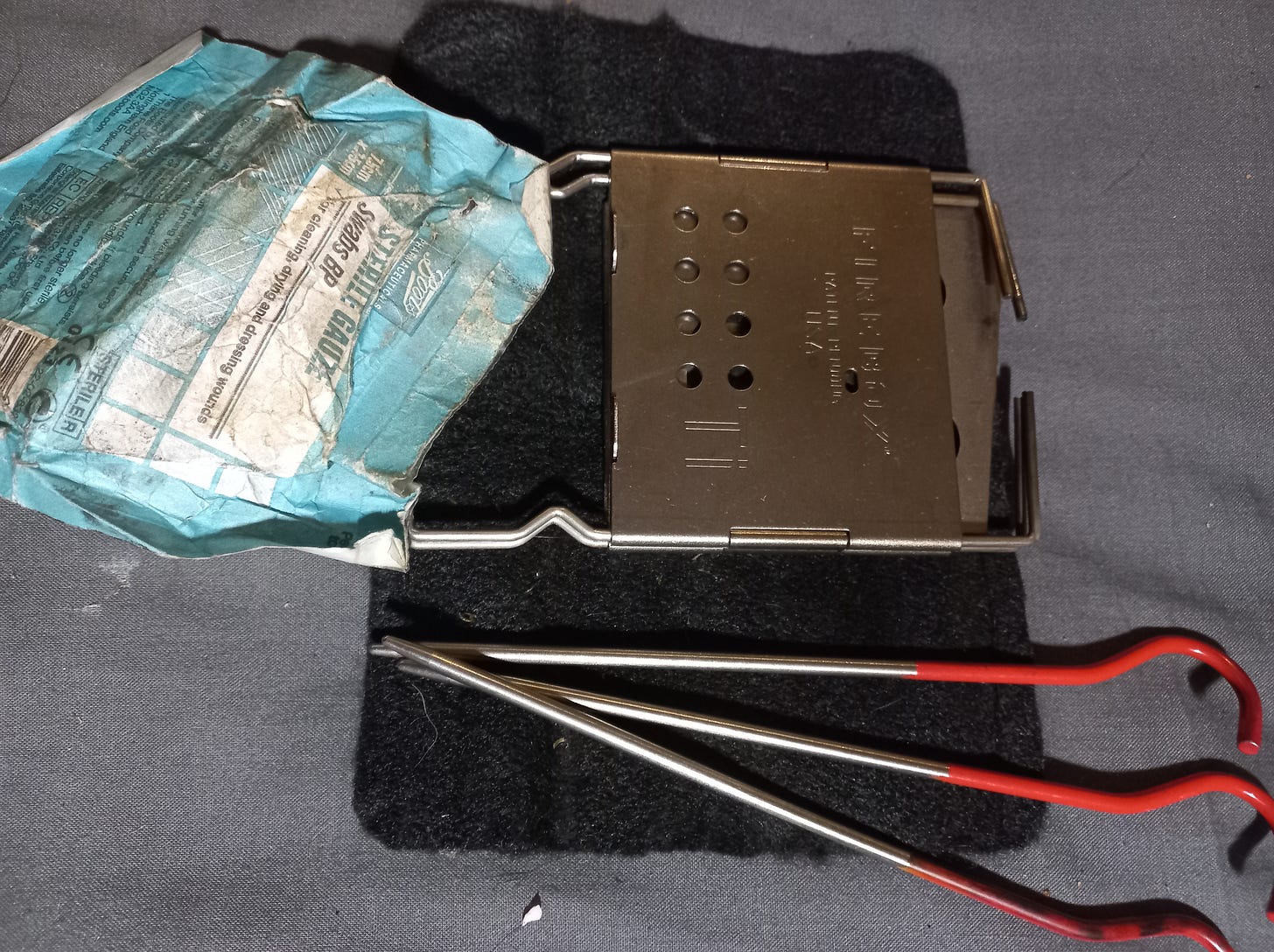

Bag back pocket contents: sterile gauze; 3 titanium stakes; stove (folded flat) with fireproof cloth which folds in half to the size of the stove.

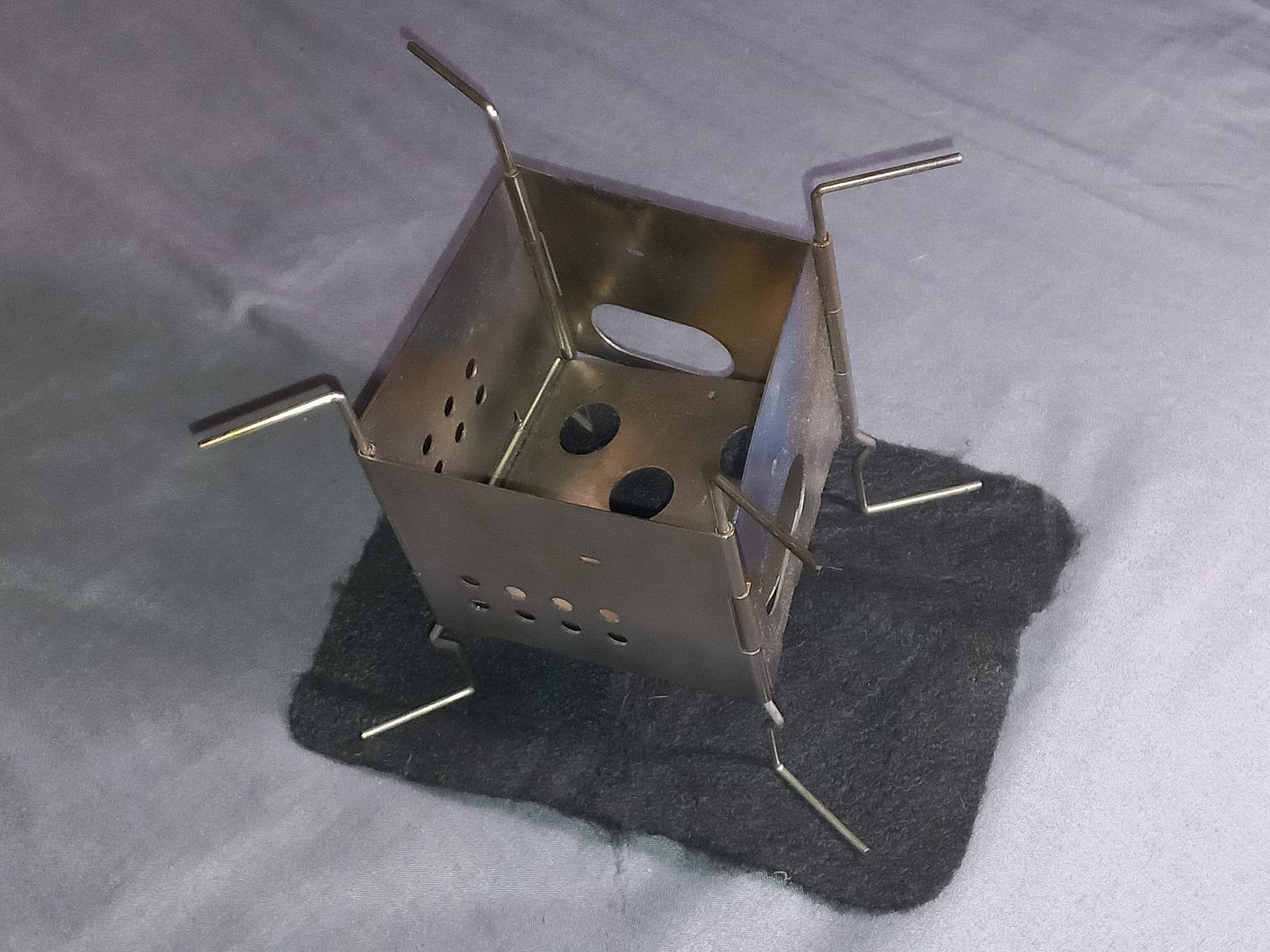

The handbag also usually contains a titanium "Firebox nano" stove (in the back pocket), a 100 ml bottle of alcohol (or meths); and an alcohol burner, consisting of something to hold the alcohol - an aluminium screw-topped can with fire-proof cloth in it.

Alcohol burner

Here you see it in use in a game park in Botswana. I was glad of the little bottle of alcohol I had in my handbag, since that bottle of meths in the photo (sold for cleaning) which I had bought locally was too watered down to burn!. The smaller bottle that you see here has a screw top for security, and a plug in “dropper” or "squirter" fitting which you can take out for refilling; but with the small hole you can squirt alcohol into the stove as its runing out, so that you don't have to wait for things to cool down before you refill and relight it. The fine stream of alcohol moves much faster than the flame can travel along it! NOT that I'd ever suggest anyone else did anything so foolish as to squirt liquid fuel at a flame! That would be very irresponsible! (And of course alcohol is the only fuel I would do this with, not kerosene nor diesel and obviously not petrol, which would dissolve the bottle).

With an alcohol burner, and the means to put the pan over it, it is easy to heat some water discretely for a hot water bottle and a hot drink, with minimum noise, movement, smell, or flames. The firebox even cuts down all these things (to a lesser extent) when using twigs as fuel, as well as reducing the amount of fuel (twigs) you need by about 90% compared to a wood fire on the ground. I fold it in the piece of black fireproof cloth (that came with it). That cloth goes underneath to catch any ash or embers when using twigs.

Firebox titanium nano

Being able to heat water means that you can sterilise it if you don't have a filter for some reason.

List of Contents

Some details of the bag contents vary from time to time, but I take

Tools

Knife: a multitool - Leatherman juice (153g - quite small as I'm carrying it a lot) This model includes a plain and a serrated blade, saw and a really excellent and useful file with two roughnesses and an edge that functions as a hacksaw. (The spoon is helpful for digging).

Light: a headtorch - (Fenix LD15R) with 2 spare batteries. (Even though it’s aluminium rather than lighter weight plastic, I got fed up with plastic ones breaking, especially if they had a hinge). [Edit: nowadays I’ve moved this to my lightweight rucksack due to the Rovyvon keyring one.]

lighter and “relighting” candles in a titanium screw-top container

Food/water

water canteen and cup capable of being heated

a titanium spoon (a stout one that used to have a fork at the other end which I sawed off, so it's easy to stow. I don't like sporks of either sort).

sometimes protein bars instead of the firebox stove, in which case you can stick the 3 titanium stakes in the ground to support the cup over the flame.

Fuel and stove to heat water

Shelter

emergency blanket (larger & more robust than some) secured with elastic (which I sewed in) in the unused space next to the neck of the canteen.

Elastic sewn to hold emergency blanket. (The mesh pocket would be too flat).

Maintenance & Repair (self & kit)

sterile gauze and two or three tampons, super-glue, alcohol (for sterilising), Disprin (pain and clots), Fexo (antihistamine)

sewing kit; duct tape and insulating tape around a card. Glue stick (melt with the lighter). Zip ties. Wire (pike-fishing line).

soap, towel (the yellow absorbent cloth) & razor (Bic 2 with handle largely snapped off); toothbrush, toothpaste & nailbrush (a "smoker’s" hard toothbrush, handle snapped off); insect repellant and sunblock (each in its own aluminium screw-top pot)

sometimes a small pot of vaseline: cheap maintenance for leather shoes

Second side pouch contents: lead to charge phone & torch; torch with 2 spare batteries & tritium light; soap in screw-top pot; razor; compass; leatherman juice; glue stick; tampon; alcohol burner; lighter and candles in titanium pot; 100 ml alcohol or meths. The other 2 aluminium pots (insect repellant & sun-screen) are tucked between the main pouch and where the strap joins.

Information

communication: pen, sharpie, pencil, a piece of paper, whistle, phone

navigation: compass, phone with downloaded maps

if not clipped to me, keys are clipped to the ring at the back.

Defense & concealment

I don’t normally carry such a thing in this bag, but since the pocket at the back has an open bottom which is held shut with powerful hook-and-loop strips, you could keep a sheath-knife there: certainly a neck knife.

For a smallish handbag this is a great kit to have with you when traveling:

You can shave, and wash all over (see "Be Prepared 3"), so if you're changing flights in London, and want to wayou don't need a new mortgage.

You can have a bottle of water that isn't going to poison you over the decades with plasticisers (or aluminium) if you use it every day.

You can cook and eat most food with a spoon and knife, pan and lid.

If you're staying in an unfamiliar house you have a pot to pee in if you don't want to wander round at night and disturb people!

You can dig quite effectively using the spoon as a pick and the canteen cup as a shovel. (E.g. I once buried about 15 yards of our electric extension cable in a campsite, so that a neighbour could drive over it).

Using the handle as a pick is surprisingly comfortable

a shovel (as well as pot, pan, cup, bowl, basin, warmer …)

You can warm up with a hot drink.

When you go to bed you have with you several things that people commonly want at their bedside:

a drink of water

your phone (on airplane mode, of course)!

a torch

keys (with an alarm remote control, in my case) ...

pencil and paper for those brilliant middle-of-the-night ideas.

5 Training

I.e. completely weightless things your have with you - in your brain and body!

There’s an old joke about the young Yehudi Menuin, a prodigy on the violin, who is due to play in Carnegie Hall for the first time at the age of twelve, and makes his way to New York by himself. Unsure whether to walk or go by public transport he catches the eye of an elderly man who, by co-incidence is Robert Davidovici, a famous violinist. “Excuse me sir”, says the boy carrying the violin-case, “can you tell me how to get to Carnegie Hall”?

“Practice, practice, practice” is the answer.

Don’t wait until you have to sleep outside in an emergency before you go backpacking! You’ll sleep much better and be in a calmer state of mind if you’ve had some practice. You can do some in your garden if you have one. (Also see Be Prepared 3)

Practice with a slightly heavier pack than you want to take. Work up to it gradually if necessary.

Look into how to train your body to metabolise fat rather than sugars, then increase the time before breaking your fast. You can progress to two then one meal a day in the evening without feeling hungry at all. It’s not only good for your health, but saves you a lot of time and money as well. This doctor - “Dr. Boz” on YouTube - seems reliable, although it takes some time to take in the whole picture.

Get rid of ANY addictions you have. An emergency is not the time to be doing without your drug of choice for the first time, is it? Don’t have any? Great! Now go without coffee for the next month! If that’s a problem for you, what does that tell you? (Incidentally, if giving up coffee, do it gradually over 2 weeks, not cold turkey).

Final tip: Discuss with other members of your household where to rendezvous in an emergency. You might want to have two places: one quite nearby, and one a long way away, where you have some food etc. cached.

For more articles like this, go to the homepage (click on the title - “What Do I No”) then the “Practical” tab - either read or listen

The main reason that wool has a reputation for insulating when wet is that woollen yarn isn't twisted tight, squeezing out the air spaces in the yarn, is it? Tim Severin, who reproduced the voyage of Saint Brendan, by crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a small, open boat made of leather, did a lot of research into wool versus man-made fibres, and largely came down in favour of wool. But - and this is a significant but - all his wool clothing was drenched in water-repellant sheep-grease - lanolin. Are you really going to do that with your everyday clothes? Man-made fibres are mainly somewhat hydrophobic: i.e. if they are clean they are not wetted so much as clean wool is: they absorb and adsorb less water. If you do use wool, consider the water-repellant treatments you can give them, like Nikwax.