Two Tips for Long distances on Foot

Enjoy walking in the country? Keeping fit? Planning to "bug out"? Training for a marathon?

1 Egyptian Tally

2 Mixed gait

3 More details on each

About a year ago I was in Botswana, and did something really stupid. (In my head I hear a chorus of “what’s new?” from friends and family).

For me it was yet another reminder of my view that although some people may have the odd flash of being quite good at something in a limited way, the overall stupidity of humans soon re-asserts itself! ( I explore that notion - which I think is of central importance - in

But I’ll come back to that stupid incident later.

Tip 1: Keeping Track of How Far You’ve Gone

Reading a map is a useful skill which needs practice. If you’ve any experience of it at all, you will appreciate the need to keep track of how far you have gone. (I’m assuming you appreciate the value of not relying on a phone)! There’s a lot online about different aspects, but I’ll restrict myself to something you may not have come across.

Most people know about counting your paces. A typical adult will put their left foot down about 60 - 70 times in walking 100 m. So by counting your paces you know how far you’ve gone. Instead of counting up into the thousands and millions, it’s better to count the

paces up to 65 (or whatever 100 m is for you);

keep a tally of how many 100 m you’ve done up to 10 (i.e. 1km); then

keep a tally of how many km’s you’ve done.

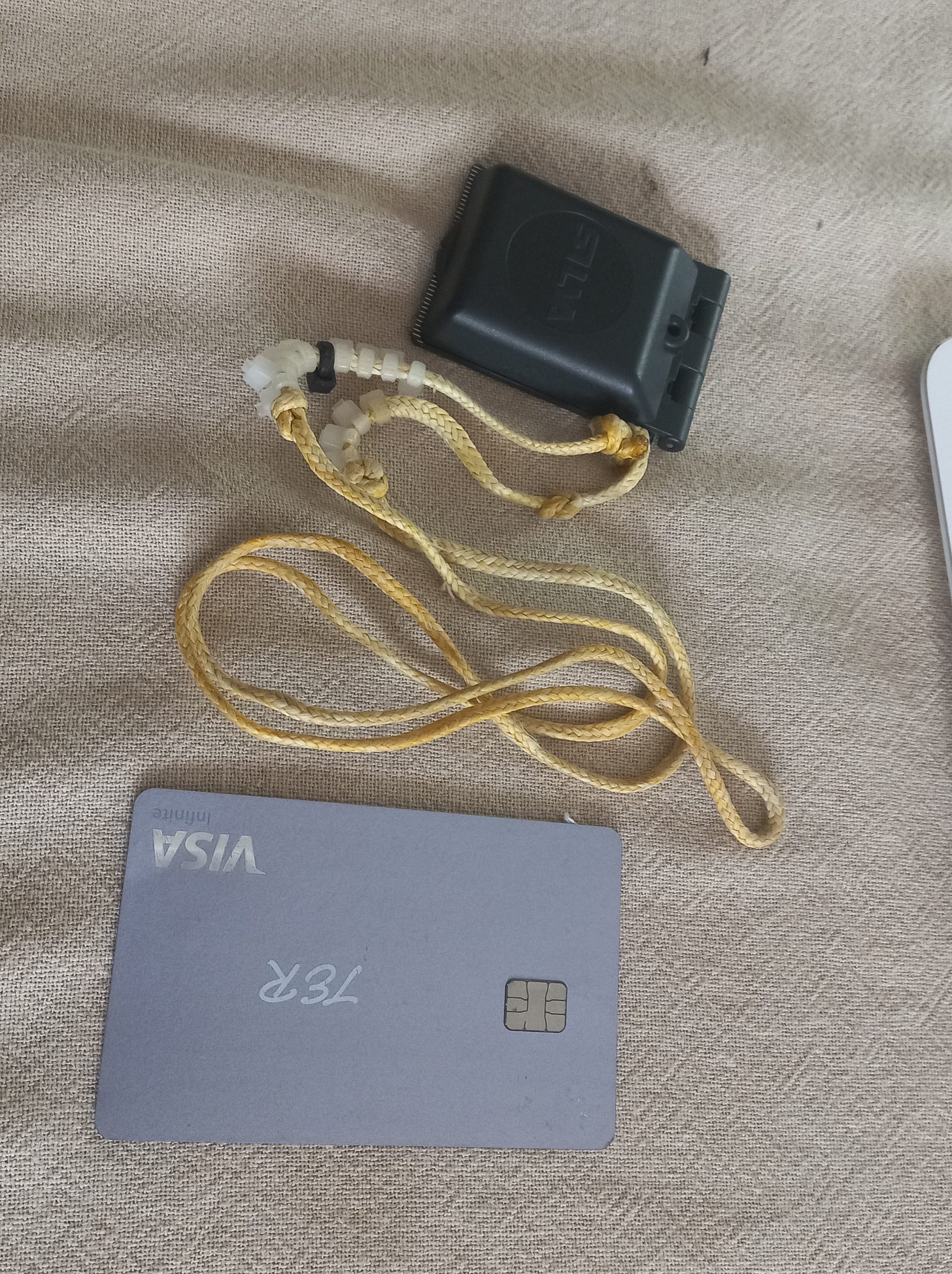

As many of you will know, a convenient way to do the latter 2 is with “pace beads” or “Ranger beads”, a simple abacus on a string:

The loop on the end of this string can be passed through a button-hole, then the other end passed through the loop.

After 1 x 100m you pull 1 of the lower 9 beads down till it touches the knot;

after 2 x 100m you pull down the second one to touch the first, etc.

After 10 x 100 m you pull all the nine beads back up, and pull down 1 of the 1km beads.

4 + 9 beads is the usual arrangement, which enables you to gauge up to 5 km.

This is one I made from a lace which goes around the neck. The large beads are easy to use with gloves on. They sell them in craft shops. (The metal pieces are a small cerium rod (the “flint” material from a lighter) and a striker. These go happily through an airport security check).

Here’s a small set easily made from string and the smallest cable-ties (zip-ties) I could find. Rubbing some beeswax on the string means they move easily when you want them to, and stay still when you don’t.

The set is small and light enough to live in a shirt pocket virtually unnoticed by the wearer in terms of weight or bulk. (The compass is a Silva Ranger SL).

This much is common knowledge. My suggestion is for how to count the sixty-odd paces for 100m!

Now, you may think that you can count up to 70 without any problem, and I’m sure you can. The problem comes after you have counted up to 66 (e.g.) successfully, several times, when inevitably the counting is on “autopilot” after a while in your head, and you suddenly notice yourself saying “92, 93, … blast! I should have stopped at 66”!

Or when really on autopilot, while thinking about something other than counting - something you may well have to do - you might wonder if you left out 10 or 20 counts, because it feels as if that 100 m was very short; and you lose confidence in your measure.

And who wants to concentrate on counting the whole time? You will have more urgent or important or enjoyable things to think about!

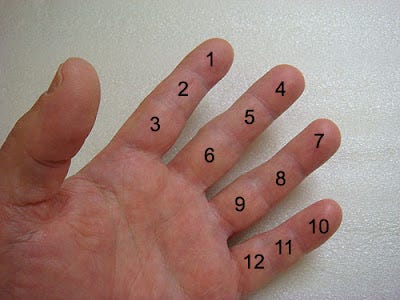

Instead of counting in your head you can use the Ancient Egyptian method of keeping tally, which is much more reliable, and with a little practice can soon happen automatically, on muscle memory, leaving you free to think. Using your thumb as a pointer, you touch each bone of your fingers in turn, as your left foot touches the ground.

This therefore indicates 5 paces:

When you run out of finger-bones at 12, you keep a tally of the twelves (dozens) with your other hand (let’s say the right hand). This is a simpler system: you just point to each finger tip in turn with your right thumb. For the first dozen you are not indicating a finger at all (zero dozens so far). When you have run out of the four fingers (plus zero fingers) on your right hand, you have done 5 x 12 which is (conveniently) 60, about right for 100m.

The person who first told me that this was how the Ancient Egyptians kept a tally of how many bushels of wheat (or whatever) someone was putting into the common granary was something of an expert on things Ancient Egyptian; but although I’m getting on in years, I wasn’t there, and don’t really know if this is true. But the method seems very plausible, and was affirmed by the horologist that I stole the numbered fingers diagram from.

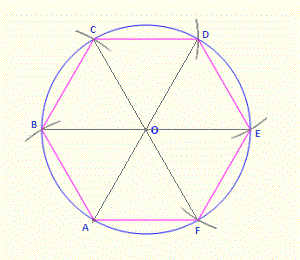

This partly explains the Ancient Egyptian (and hence our) habit of counting things in twelves and sixties: sixty seconds in a minute; sixty minutes in an hour; 12 hours in a day or night; 12 months in a year; 60 degrees in the angles of an equilateral triangle, 6 of which fit naturally together to make up a “circle” of 360 degrees

… which is also about the right number for the “circle” of days in a year (plus 5 days holiday). Navigators needing more precision than the nearest degree divide a degree into 60 minutes then 60 seconds of angle.

Well, true or not - it’s very “handy”.

Sixty will be about the right number for long-legged people on easy terrain. Other people can then just count (in their head in the normal fashion) an extra 4 steps, or whatever is necessary.

After you have done your 100m your left hand continues its tally, and your right hand is now not doing anything for the first dozen, and is free to pull down one of the pace beads.

When you have mastered this, it means your walk will be more interesting, as you are free to think for most of the time, instead of trying to concentrate on just counting - and inevitably failing, since the mind soon rebels at doing something so repetitive.

Rather than try and do all this right from the beginning, I would suggest first practising the tally of 12 only, while walking. After a few days of doing this it will be automatic. You can train each hand to do this.

Then introduce both hands, tallying up to 60.

Then get yourself a programme like Gaia on your phone, which will show you how far you have walked. First, on level road, find out how many steps it takes you to cover 100m. (I haven’t done much research: Gaia works well for me; there may be better programmes).

When you can do that reliably, and you find that you get to 1 km pretty accurately, then change the terrain: go for somewhere with a long uphill, so you can see how many steps it takes you to do 100 m on that slope, and then downhill, and see how many that is.

Then try on rougher terrain; different gradients and so on.

At the beginning of each 100 m, you look ahead and estimate how many steps you will take for 100 m on that terrain, and check with your phone how accurate you were at the end of each 100m.

It’s an interesting challenge of an exercise, which gives you a useful skill when navigating somewhere you don’t know well, without relying on a phone.

There are more detailed tips on this after the second item.

(I’m reminded of an episode from David Mitchell’s autobiography in which he goes to a doctor about lower back pain. Eventually the doctor asks him “do you really want to cure your back pain”? David gives a puzzled assent. “Then go for a two-hour walk every evening!” David followed the advice and found that it worked, not to mention made him familiar with his surroundings, and - presumably - makes one fitter and slimmer into the bargain).

Tip 2: Mixed Gait

If a horse is walking slowly and you encourage it to speed up (or it decides to do so for itself) it can wask faster … and faster … but eventually it will break into a trot, and you get bumped up and down in 2/4 time (musically speaking). If it wants to go even faster it will break into a canter, making progress in 3/4 time; and eventually into a gallop - in 4/4 time like the walk, but more rapid and only having one foot touching the ground at any one time instead of three. (Very small horses or large dogs have a fifth gait available between walking and trotting, called “pacing”, where the legs on each side move together, like two soldiers marching in step). I imagine that proficient riders can “tell” a horse to break into a canter or whatever, but even without telling, the horse - whether ridden or not - if it wants to go faster, will change gait automatically. This is because it is more efficient, more ergonomic.

Humans, being restricted to two legs, have a more limited range of permutations. If we disregard hopping and skipping which I guess are not really gaits, we have only walking and running.

If you ever watch the olympics e.g. you may have come across walking races.

Officials watch the candidates carefully to check that they do not break into a run: there should always be a foot touching the ground, with no air-time as in running. To break into a run is cheating.

What does this tell you about the efficiency of walking at this speed? If to run is to cheat, clearly it is more efficient to run. You can easily convince yourself of this (if you are suitably able) by walking faster and faster until it’s as fast as you can. As you approach your limit it becomes clear that the amount of effort you put in for each little increment in speed becomes larger and larger; breaking into a run is a relief!

Well, suppose that you are out for a long walk - (and that could be an hour’s walk or three day’s walk e.g.) - but you want it to take less time than it would if you walk at normal speed.

Well one solution, used by armies the World over, is to walk faster. However a more efficient method is to mix running with walking at a normal pace. (This is probably not appropriate when you are carrying a lot, e.g. a heavy machine gun part or backpack).

One technique is to run for 15 paces then walk for 15 paces; then repeat. I find 15 a suitable number. If the number is too small, it is less efficient; if the number is too large then you approach the … let’s call it the “out-of-breathness” that you get with running.

I’ll go into more detail about “How” in a moment, but first - more “Why”.

As implied above, you will save energy if you need to go a bit faster than comfortable walking speed. If it’s for a long way, the saving on calories expended could be significant.

A simple way to demonstrate this is to use Gaia or a similar programme (or just time yourself over a particular route) to see how fast you are going before you have to start panting - breathing through your mouth rather than nose. (I.e. make sure you don’t pant). The onset of panting indicates quite accurately a certain rate of energy expenditure (for you, on that day). Do this for walking and also for mixed gait. Certainly in my case, I go faster on average with the alternating gait when keeping at a rate I can sustain without panting.It feels rather like getting something for nothing: because you cover most of the distance at a run, but spend most of your time walking!

This is because your stride is longer when you run: so if you do equal numbers of paces walking and running (15 at a time) you cover more distance in the run phase.

Similarly, you will find that the frequency of your footfalls is higher when at a run: so 15 paces at a run takes less time than 15 at a walk.

Suppose you need to go to somewhere on foot and it’s going to take two or three days, and you want to get there as soon as possible. Well, unless you’re one of the very few people whose body is robust enough to run for two days and still be functioning adequately on arrival, then this is the way to do it. Wear and tear is far less when walking, and I suspect (although I can’t be sure) that the walking phase intersperced with the running is less hard on the knees for example than a solid run and solid walk of the same total distance. Those frequent breaks from the incessant pounding may well allow some sort of recovery.

I find that I’m about 25% - 33% faster (depending on the terrain) using mixed gait at a comfortable pace than walking at a comfortable pace. I find I’m about 10% faster using mixed gait than walking as fast as I can, even though the walking phase of the mixed gait is much less energetic than walking as fast as possible: it feels like a saunter!It’s a good technique as part of a warm up for a run, so that all the tendons and joints are well lubricated before you really exert yourself.

Another variation on the wear-and-tear theme: you may be recovering from an injury, and be at a stage where you can do this for a while, but running for that amount of time would set back your injury.

A special case of “recovering from an injury” - although one doesn’t normally think of it as such - is the next session after pushed your boundaries in a training session, where you ran faster or further than normal. You need something easier while your recover from that hard session.

Similarly if you are getting on in years recovery is slower. ALL exercise causes damage, which your body then repairs - in fact over-repairs - so that you get stronger. This can be a way to be vigorous and active when running is no longer possible for the same amount of time in a week.

If you are training for a long run like a marathon, nowadays it is well-known that you have to do most of your training as “Long, Slow, Distance” (LSD) - much less demanding than the speed you eventually hope to run at. This is because you have to build up the strength of the tissues that are NOT muscle - the cartilage, ligaments and tendons, even bone. These are much less vascular (less well supplied with blood vessels) than muscle, so they get stronger much more slowy than muscle (including your heart of course) which can get stronger quite quickly. So it takes months of that slow process of causing a tiny amount of damage with exercise - not too much - followed by the over-repair in the recovery phase before your next run. Getting the balance right between too much damage with not enough recovery on the one hand, and not enough exercise to stimulate growth in strength on the other is always a delicate problem. Given the length of time needed to train for a marathon, it can be quite a long time before you get the feedback that you are overdoing things. Personally I have always prefered to err on the cautious side, since over-doing things sets you back for a long time, possibly permanently. I feel it is better to be patient, and content to keep improving, rather than improve at the maximum possible speed. (But if you want to compete seriously in the short term, this would not be the optimum strategy).

A drawback, it seems to me, of the training strategy of mainly LSD plus a little speed-work (i.e. short distances faster than marathon speed) is that you never practice the speed you hope to race at. Practicing something you want to improve needs to be very specific.

So an additional string to your bow is to include some mixed gait in your programme. Starting from a low level of fitness, suppose that first you walk more and more, until you get to the point of being able to walk the distance of your half-marathon or whatever. Then you could start doing the mixed gait at increasing distances until you do can that to the full distance. Then you could increase the proportion of running - say raise the running part of the cycle from 15 to 20 paces (while always keeping the walking part of the cycle at 15). Then 25, 30 and so on. In this way you can practise the actual speed you want to do in a race, without overdoing it. (Long distance runners will know that you then need to “taper” for a while before the race).Mixed gait - at a rate of exertion that’s less than that which necessitates panting, yet which is significantly faster than walking - has the advantage of being very economical on water, if that is in short supply.

Now we come to my episode of more stupidity than usual in Botswana. When you breath through your mouth, bypassing your nose, you lose water very fast (as any long distance runner can tell you). It’s in your nasal cavity, as the air passes the turbinates, that heat and water are exchanged, so on arrival in the lungs the air is warmer and humid. As you exhale the reverse exchange happens to some extent, and some water recovered. Also there is the obvious increase in ventilation of the lungs, with larger breaths.

One morning I had gone out for a gentle run. Since it was a run, and I had no plan other than wander around for 40 minutes or so, I was carrying almost nothing. I found, after about an hour, that I had wandered towards a landmark that I wanted to visit sometime. I thought “well I’m about half-way there now: it would be good use of time to go the rest of the way”.

That was yet another testament to the grossly underestimated propensity for wishful thinking that we have. [See “Coping with Disagreement and Being Wrong”.]

Let me explain. In Botswana at that time of year it was quite hot, but more than that, the humidity was about zero. This was great for drying laundry on the line in about 20 minutes, but it has a similar effect on human lungs and sweat. Also, I wasn’t half-way there, I was about a third of the way there. So I didn’t have 3 times what I had already covered to do to return home, but about 5 times. What’s more the vegetation became thicker and the route therefore more convoluted. In other words it was going to take me about another six hours before I could get back and get a drink.

For some reason I have almost no sensation of thirst. This had got me in trouble about 15 years earlier, when I had been busy travelling for a couple of days and a night, finally arrived home in the evening exhausted, and therefore ate out. The meal would therefore have been more salty and sugary than I would normally eat. The following morning as I went to the gym it occurred to me that I didn’t remember drinking after first thing in the morning the previous day. So on arrival at the gymn I drank a large amount of water … again - stupidly: the more dehydrated you are, the more important it is to recover gradually. Soon after starting exercise I had a TIA (mini stroke), the only time such a thing has happened to me. I soon recovered the blood flow to whichever part of my brain was going without, but it was a salutary warning of the danger of getting dehydrated.

Now it should be clearer just how stupid I was being, going out in those conditions without the possibility of any water for about 7 hours including an hour’s run. By the time I got to the landmark I was rather scared at how dehydrated I was, and was going to be.

After the stupidity of my decision eventually sank in, I adopted the strategy of mixed gait running, at a speed in which I didn’t have to pant, in order to get home as soon as possible. I was glad to have practised this.

I was very relieved to get home without mishap, although I could tell I was severely dehyrated, which I mainly discerned not by a sensation of thirst but of tiredness, and the sight of my sunken eyes in the mirror. I spent the next 3 hours or so sipping water, to rehydrate at a reasonable rate.

Here are some tips on details

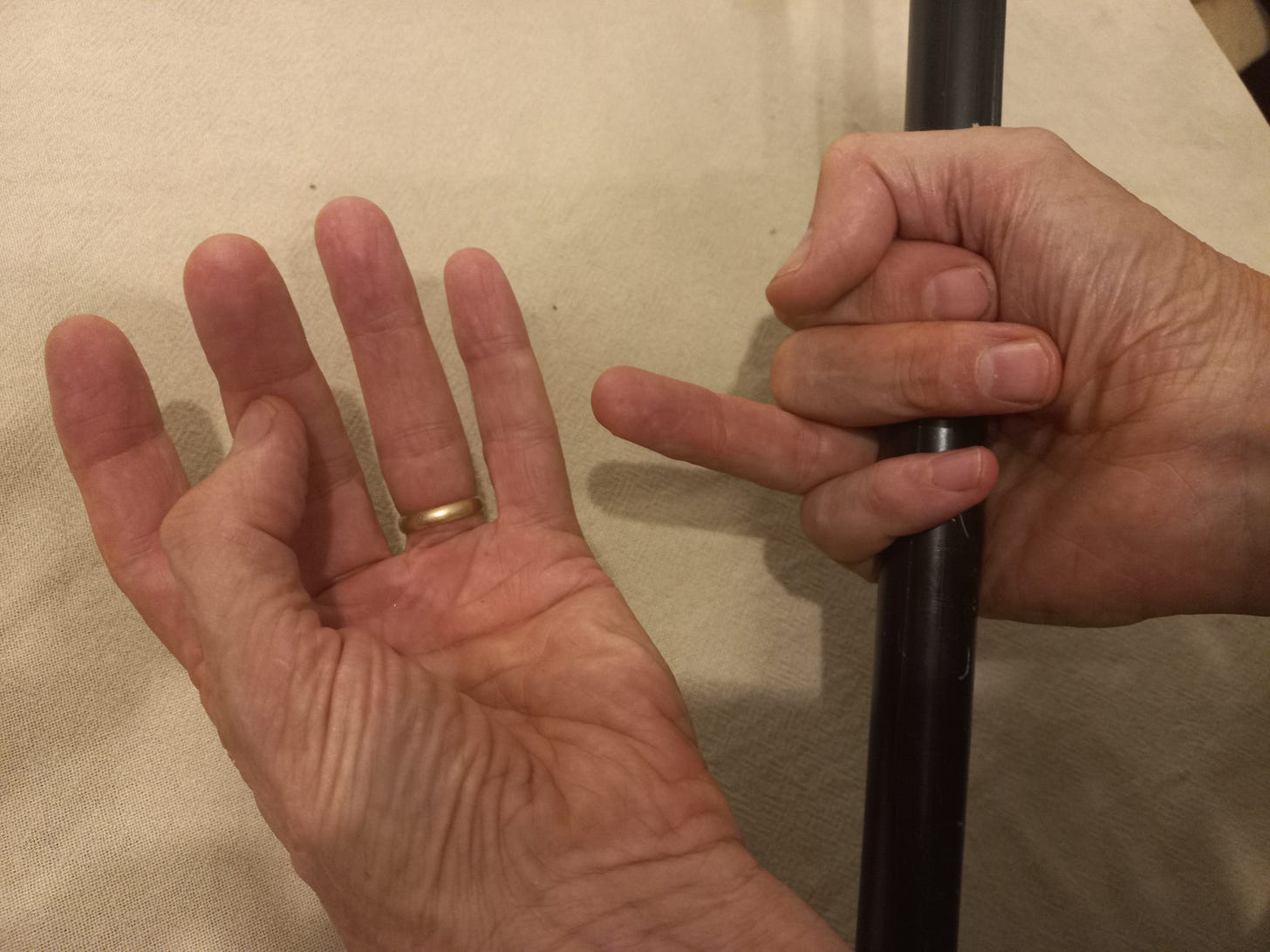

You can’t really do this with a walking pole in each hand. If only one hand is holding a staff or umbrella or something, then it is easy to do the tally of 12 with the hand that is NOT holding anything, and hold out one finger when necessary with the other instead of pointing to it with the thumb.

[The right hand shows that you have completed 3 dozens out of 5, and the left hand shows that you have done 5 of the next dozen steps]

If you use as many as 72 paces (or more) per 100m then you can use your right hand to count six of the dozens, in a similar way to above. If you are tallying paces on the left hand, then count six dozens on the right: hold out zero fingers, then your thumb, then index finger …

5 digits + zero digits for the first dozen, gives 6 x 12.When you use the Egyptian tally for measuring how far you are walking, I find one is less likely to lose track if you snap the thumb quickly to the next position, rather than tend towards drifting down the finger over 3 paces.

When switching to the walk half of the cycle, don’t be tempted to walk too fast. This is supposed to be a time when you are recovering from the run, so that it never becomes necessary to pant. Saunter!

Suppose you are using your left hand to track each pace: you move it each time your left foot (e.g.) hits the ground. When you move the right thumb, indicating another dozen is complete, it must not be on the usual (left leg) footfall, or you are counting 13 rather than 12. So that moves on a right footfall. It feels like this - “… 9, 10, 11, 12 AND 1, 2, 3”. The right thumb moves on AND.

If you find yourself needing to keep track of your distance travelled and you don’t have any ranger beads or even a piece of string to tie knots in, instead of mentally counting your paces, this technique enables you to use your fingers as described above to tally each 100 metres, so that mental counting is now available to keep track of how many 100m (tenths of a km) you have done.

If you are training for a marathon or half-marathon, or simply like going for long runs, then you can take a route that you use regularly, note the position of each kilometre completed, then, when you do that route in future, take note of how many paces each kilometre takes. You get a useful way of seeing how far you have run, and also a little insight into how efficient your running is on different kilometres and different days.

Combining the two methods, to keep track of how far you go when alternating walking and running, I have found a satisfactory method is to use the Egyptian tally up to 12 for the running phase, then (instead of counting the remaining 3 steps) mentally say the phrase “jog, jog, walk” as you slow. Of course you don’t put effort into actually slowing yourself, merely stop putting in the effort to run, and over those last 3 paces you decelerate naturally. Then you use the Egyptian tally up to 12 for the walking half of the cycle, then mentally say the phrase “pay attention now” to take you up to 15 steps. That “pay attention now” cues me to pull down the next bead, and perhaps consider something like “about how far am I towards my next waypoint”, rather than absent-mindedly drifting on and overshooting.

I found to begin with that I was apt (when attention inevitably wandered) to confuse whether I was supposed to be pulling down a bead at the end of a walk part of the cycle or run , when I would count the extra 3 steps to 15 mentally “one, two, three”: autopilot got unreliable. It’s better to avoid any counting.

I find 7 cycles will take me 2km, reasonably accurately on the flat; but “your mileage may vary”!

"For me it was yet another reminder of my view that although some people may have the odd flash of being quite good at something in a limited way, the overall stupidity of humans soon re-asserts itself!"

🤣

No... YOU wait....

I feel I just bumped into another brother from a different mother.

Different countries. Similar miscalculations and mishaps. 😁

Back to reading now.

So, I want you to know that your previous article inspired me to post the one I posted about trees.

Moreover, I want you to know this - I like to keep track of where I've been walking and I like to hike as much as the next fella. So your advice, council and sentiment is appreciated by me even though I know I still have not practiced the knots.

~

I think appreciating simple things is a good way to meditate......think about the little things that form the basis of our day-to-day existence.

~

So thanks - thank-you.

My tree link, my favorite post of my own and my Substack Place is here:

https://buffaloken.substack.com/p/trees-planted

I'm not trying to "advertise", that post I made on that link truly was informed by what you posted on an earlier article. So, I think that is communication in action.

~

Sincerely,

BK